(Podcast version here, or search for “Joe Carlsmith Audio” on your podcast app.

This essay is part of a series that I'm calling "Otherness and control in the age of AGI." I'm hoping that the individual essay can be read fairly well on their own, but see here for brief summaries of the essays that have been released thus far.)

Earlier in this series, I discussed a certain kind of concern about the AI alignment discourse – namely, that it aspires to exert an inappropriate degree of control over the values that guide the future. In considering this concern, I think it's important to bear in mind the aspects of our own values that are specifically focused on pluralism, tolerance, helpfulness, and inclusivity towards values different-from-our-own (I discussed these in the last essay). But I don't think this is enough, on its own, to fully allay the concern in question. Here I want to analyze one version of this concern more directly, and to try to understand what an adequate response could consist in.

Tyrants and poultry-keepers

Have you read The Abolition of Man, by C.S. Lewis? As usual: no worries if not (I'll summarize it in a second). But: recommended. In particular: The Abolition of Man is written in opposition to something closely akin to the sort of Yudkowskian worldview and orientation towards the future that I've been discussing.1 I think the book is wrong about a bunch of stuff. But I also think that it's an instructive evocation of a particular way of being concerned about controlling future values – one that I think other critics of Yudkowskian vibes (e.g., Hanson) often draw on as well.2

At its core, The Abolition of Man is about meta-ethics. Basically, Lewis thinks that some kind of moral realism is true. In particular, he thinks cultures and religions worldwide have all rightly recognized something he calls the Tao – some kind of natural law; a way that rightly reflects and responds to the world; an ethics that is objective, authoritative, and deeply tied to the nature of Being itself. Indeed, Lewis thinks that the content of human morality across cultures and time periods has been broadly similar, and he includes, in the appendix of the book, a smattering of quotations meant to illustrate (though not: establish) this point.

But Lewis notices, also, that many of the thinkers of his day deny the existence of the Tao. Like Yudkowsky, they are materialists, and "subjectivists," who think – at least intellectually – that there is no True Way, no objective morality, but only ... something else. What, exactly?

Lewis considers the possibility of attempting to ground value in something non-normative, like instinct. But he dismisses this possibility on familiar grounds: namely, that it fails to bridge the gap between is and ought (the same arguments would apply to Yudkowsky's "volition"). Indeed, Lewis thinks that all ethical argument, and all worthy ethical reform, must come from "within the Tao" in some sense – though exactly what sense isn't fully clear. The least controversial interpretation would be the also-familiar claim that moral argument must grant moral intuition some sort of provisional authority. But Lewis, at times, seems to want to say more: for example, that any moral reasoning must grant "absolute" authority to the whole of what Lewis takes to be a human-consensus Traditional Morality;3 that only those who have grasped the "spirit" of this morality can alter and extend it;4 and that this understanding occurs not via Reason alone, but via first tuning habits and emotions in the direction of virtue from a young age, such that by the time a "well-nurtured youth" reaches the age of Reason, "then, bred as he has been, he will hold out his hands in welcome and recognize [Reason] because of the affinity he bears to her."5

This part of the book is not, in my opinion, the most interesting part (though: it's an important backdrop). Rather, the part I find most interesting comes later, in the final third, where Lewis turns to the possibility of treating human morality as simply another part of nature, to be "conquered" and brought under our control in the same way that other aspects of nature have been.

Here Lewis imagines an ongoing process of scientific modernity, in which humanity gains more and more mastery over its environment. He claims, first, that this process in fact amounts to some humans gaining power over others (since, whenever humans learn to manipulate a natural process for their own ends, they become able to use this newfound power in relation to their fellow men) – and in particular, to earlier generations of humans gaining power over later generations (because earlier generations become more able to shape the environment in which later generations operate, and the values they pursue).6 And in his eyes, the process culminates in the generation that achieves mastery over human nature as a whole, and hence becomes able to decide the values of all the generations to come:

In reality, of course, if any one age really attains, by eugenics and scientific education, the power to make its descendants what it pleases, all men who live after it are the patients of that power. They are weaker, not stronger: for though we may have put wonderful machines in their hands we have pre-ordained how they are to use them ... The last men, far from being the heirs of power, will be of all men most subject to the dead hand of the great planners and conditioners and will themselves exercise least power upon the future.

The real picture is that of one dominant age—let us suppose the hundredth century A.D.—which resists all previous ages most successfully and dominates all subsequent ages most irresistibly, and thus is the real master of the human species. But then within this master generation (itself an infinitesimal minority of the species) the power will be exercised by a minority smaller still. Man's conquest of Nature, if the dreams of some scientific planners are realized, means the rule of a few hundreds of men over billions upon billions of men. There neither is nor can be any simple increase of power on Man's side. Each new power won by man is a power over man as well. Each advance leaves him weaker as well as stronger. In every victory, besides being the general who triumphs, he is also the prisoner who follows the triumphal car.

Lewis calls the tiny set of humans who determine the values of all future generations "the conditioners." He allows that humans have always attempted to exert some influence over the values of future generations – for example, by nurturing and instructing children to be virtuous. But he thinks that the conditioners will be different in two respects. First: by hypothesis, they will have enormously more power to determine the values of future generations than previously available (here Lewis expresses gratitude that previous educational theorists, like Plato and Locke, lacked such power – and I agree). Second, though, and more importantly, Lewis thinks that the conditioners will view themselves as liberated from the demands of conscience, and of the Tao – and thus, that the moral status of their attempts to influence the values of the future will be fundamentally altered:

In the older systems both the kind of man the teachers wished to produce and their motives for producing him were prescribed by the Tao—a norm to which the teachers themselves were subject and from which they claimed no liberty to depart. They did not cut men to some pattern they had chosen. They handed on what they had received: they initiated the young neophyte into the mystery of humanity which over-arched him and them alike. It was but old birds teaching young birds to fly. This will be changed. Values are now mere natural phenomena. Judgements of value are to be produced in the pupil as part of the conditioning. Whatever Tao there is will be the product, not the motive, of education. The conditioners have been emancipated from all that. It is one more part of Nature which they have conquered. The ultimate springs of human action are no longer, for them, something given. They have surrendered—like electricity: it is the function of the Conditioners to control, not to obey them. They know how to produce conscience and decide what kind of conscience they will produce. They themselves are outside, above.

Lewis gives another example of this sort of distinction earlier in the book: namely, a Roman father teaching a son that it is sweet and seemly (dulce and decorum) to die for his country. If this father speaks from within the Tao, and believes that such approving attitudes towards a patriotic death are objectively appropriate and warranted, then he is passing on his best understanding of the True Way, and helping his son see and inhabit reality more deeply. But if the father does not believe this, but rather thinks that it will be useful (either for his own purposes, or for the purposes of society more generally) if his son approves of patriotic self-sacrifice, then he is doing something very different:

Where the old initiated, the new merely "conditions". The old dealt with its pupils as grown birds deal with young birds when they teach them to fly; the new deals with them more as the poultry-keeper deals with young birds— making them thus or thus for purposes of which the birds know nothing. In a word, the old was a kind of propagation—men transmitting manhood to men; the new is merely propaganda.

Condor Teaches Youngster to Fly (Narrated by David Tennant) - Earthflight - BBC One

Old birds pushing young birds off of cliffs. Wait sorry remind me what this has to do with meta-ethics again?

The conditioners, then, are to the future as poultry-keepers with unprecedented power. And absent guidance the Tao, on what grounds will they choose the values of their poultry? Here Lewis is quite pessimistic. In particular, he thinks that the conditioners will likely regress to their basest impulses – the ones that never claimed objectivity, and hence cannot be destroyed by subjectivism – and in particular, to their desire for pleasure for themselves. But this is not core to his thesis.

More core, though, is the claim that however the conditioners choose, their apparent conquest over Nature will in some sense amount to Nature's conquest over them, and hence over humanity as a whole. This is one of the more obscure aspects of Lewis's discussion – and its confusions, in my opinion, end up inflecting much of the book. Lewis seems to hold that somehow, by treating something as a part of Nature – and in particular, by treating it purely as an object of prediction, manipulation, and control – you in fact make it into a part of Nature:

The price of conquest is to treat a thing as mere Nature. Every conquest over Nature increases her domain. The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them: the soul does not become Nature till we can psychoanalyse her. The wresting of powers from Nature is also the surrendering of things to Nature ... if man chooses to treat himself as raw material, raw material he will be.

I'll return, below, to whether this makes any sense. For now, let's look at Lewis's overall conclusion:

We have been trying, like Lear, to have it both ways: to lay down our human prerogative and yet at the same time to retain it. It is impossible. Either we are rational spirit obliged for ever to obey the absolute values of the Tao, or else we are mere nature to be kneaded and cut into new shapes for the pleasures of masters who must, by hypothesis, have no motive but their own "natural" impulses. Only the Tao provides a common human law of action which can over-arch rulers and ruled alike. A dogmatic belief in objective value is necessary to the very idea of a rule which is not tyranny or an obedience which is not slavery. (Emphasis added.)

Lewis finishes the book with some speculations on the possibility of a form of science that somehow does not reduce its object to raw material – and hence, does not extend Nature's domain as it gains knowledge and power. "When it explained it would not explain away. When it spoke of the parts it would remember the whole. While studying the It it would not lose what Martin Buber calls the Thou-situation." But Lewis is not sure this is possible.

Are we the conditioners?

I'll object to Lewis in various ways in a moment (I think the book is often quite philosophically sloppy – sloppiness that Lewis's rhetorical skill can sometimes obscure). First, though: why I am interested in this book at all?

It's a number of things. Most centrally, though: Yudkowsky's core narrative, with respect to the advent of AGI, is basically that it will quickly lead to the culmination – or at least, the radical acceleration – of scientific modernity in the broad sense that Lewis is imagining. That is, available power to predict and control the natural world will increase radically, to a degree that makes it possible to steer and stabilize the future, and the values that will guide the future, in qualitatively new ways. And Yudkowsky is far from alone in expecting this. See, also, the discourse about "value lock in" in Macaskill (2022); Karnofsky's (2021) discussion of "societies that are stable for billions of years"; and the more detailed discussion in Finnveden et al (2022). And to be clear: I, too, find something like this picture worryingly plausible – though far from guaranteed.

What's more, the whole discourse about AI alignment is shot through with the assumption that values are natural phenomena that can be understood and manipulated via standard science and technology. And in my opinion, it is shot through, as well, with something like the moral anti-realism that Lewis is so worried about. At the least, Yudkowsky's version rests centrally on such anti-realism.7

It seems, then, that a broadly Yudkowskian worldview imagines that, in the best case (i.e., one where we somehow solve alignment and avoid his vision of "AI ruin"), some set of humans – and very plausibly, some set of humans in this very generation; perhaps, even, some readers of this essay -- could well end up in a position broadly similar to Lewis's "conditioners": able, if they choose, to exert lasting influence on the values that will guide the future, and without some objectively authoritative Tao to guide them. This might be an authoritarian dictator, or a small group with highly concentrated power. But even if the values of the future end up determined by some highly inclusive, democratic, and global process – still, if that process takes place only in one generation, or even over several, the number of agents participating will be tiny relative to the number of future agents influenced by the choice.8 That is, a lot of the reason that ours is the "most important century" is that it looks like rapid acceleration of technological progress could make it similar to Lewis's "one dominant age ... which resists all previous ages most successfully and dominates all subsequent ages most irresistibly." Indeed: remember Yudkowsky's "programmers" in the last essay, from his discussion of Coherent Extrapolated Volition? They seem noticeably reminiscent of Lewis's "conditioners." Yes, Lewis's rhetoric is more directly sinister. But meta-ethically and technologically, it's a similar vision.

And Lewis makes a disturbing claim about people in this position: namely, that without the Tao, they are tyrants, enslaving the future to their arbitrary natural preferences. Or at least, they are tyrants to the extent that they exert intentional influence on the values of the future at all (even, plausibly, "indirectly," by setting up a process like Coherent Extrapolated Volition – and regardless, CEV merely re-allocates influence to the arbitrary natural preferences of the present generation of humans).

Could people in this position simply decline to exert such influence? In various ways, yes: and I'll discuss this possibility below. Note, though, that the discourse about AI alignment assumes the need for something like "conditioning" up front – at least for artificial minds, if not for human ones. That is, the whole point of the AI alignment discourse is that we need to learn how to be suitably skillful and precise engineers of the values of the AIs we create. You can't just leave those values "up to Nature" – not just because there is no sufficiently natural "default" to be treated as sacred and not-to-be-manipulated, but because the easiest defaults, at least on Yudkowsky's picture (for example, the AIs you'll create if you're lazily and incautiously optimizing for near-term profits, social status, scientific curiosity, etc) will kill you. And more generally, Yudkowsky's deep atheism, his mistrust towards both Nature and bare intelligence, leaves him with the conviction that the future needs steering. It needs to be, at a minimum, in the hands of "human values" – otherwise it will "crash." But to steer the future ourselves – even in some minimal way, meant to preserve "human control" – seems to risk what Lewis would call "tyranny." And if, per my previous discussion of "value fragility," we follow a simplified Yudkowskian vibe of "optimizing intensely for slightly-wrong utility functions quickly leads to the destruction of ~all value" and "the future will be one of intense optimization for some utility function," then it can quickly start to seem like the values guiding the future need to be controlled ("conditioned?") quite precisely, lest they end up even slightly wrong.

On a broadly Yudkowskian worldview, then, are we to choose between becoming tyrants with respect to the future, or letting it "crash"? Let's look at Lewis's argument in more detail.

Lewis's argument in a moral realist world

Lewis believes in the existence of an objectively authoritative morality, and the "conditioners" do not. But it's often unclear whether his arguments are meant to apply to the world he believes in, or the world the conditioners believe in. That is, he thinks there is some kind of problem with people intentionally shaping the values that will guide the future. But this problem takes on a different character depending on the meta-ethical assumptions we make in the background.

Let's look, first, at a version of Lewis's argument that assumes moral realism is true. That is, there is an objectively authoritative Tao. But: the conditioners don't believe in it. What's the problem in that case?

One problem, of course, is that they might do the wrong thing, according to the Tao. For example, per Lewis's prediction, they might give up on all commitment to honor and integrity and benevolence and virtue, and choose to use their power over the future in whatever ways best serve their own pleasure. Or even if they keep some shard of the Tao alive in their minds, they might lose touch with the whole, and with the underlying spirit – and so, with the values of the future as putty in their hands, they might make of humanity something twisted, hollow, deadened, or grotesque.

But there's also a subtler problem: namely, that even if they do the right thing, they might not be guided, internally, by the right source of what I've previously called "authority." That is, suppose that the conditioners keep their commitments to honor and integrity and benevolence and virtue, and they are guided towards Tao-approved actions on the basis of these commitments, but they cease to think of these commitments as grounded in the Tao – rather, per moral anti-realism, they think of their commitments as more subjective and preference-like. In that case, my guess is that Lewis will judge them tyrants and poultry-keepers, at least in some sense, regardless. That is, to the extent they are intentionally shaping the values of the future, even in Tao-approved ways, they are doing so, according to them, on the basis of their own wills, rather than on the basis of some "common human law of action which can over-arch rulers and ruled alike." They are imposing their wills on the raw material of the universe – and including: future people – rather than recognizing and responding to some standard beyond themselves, to which both they and the future people they are influencing ought, objectively, to conform.

In this sense, I expect Lewis to be more OK with moral realists doing AI alignment than with the sort of anti-realists who tend to hang around on LessWrong. The realists, at least, can be as old birds teaching the young AIs to fly. They can be conceptualizing the project of alignment, centrally, as one of helping the AIs we create recognize and respond to the truth; helping them inhabit, with us, the full reality of Reality, including the normative parts – the preciousness of life, the urgency of love, the horror of suffering, the beauty of the mountains and the sky at dawn.9 Whereas the LessWrongers, well: they're just trying to empower their own subjective preferences. They seek willing servants, pliant tools, controlled Others, extensions of themselves. They are guided, only, by that greatest and noblest mandate: "I want." Doesn't that at least remind you of tyranny?

If we condition on moral realism, I do think that Lewis-ian concerns in this broad vein are real. In particular: if there is, somehow, some sort of objectively True Path – some vision of the Good, the Right, the Just that all true-seeing minds would recognize and respond to – then it is, indeed, overwhelmingly important that we do not lose sight of it, or cease to seek after it on the basis of a mistaken subjectivism. And I think that Lewis is right, too, that such a path offers the potential for forms of authority, in acting in ways that affect the lives and values of others, that more anti-realist conceptions of ethics have a harder time with.10

What's more, relative to the standard LessWronger (and despite my various writings in opposition to realism), I suspect I am personally less confident in dismissing the possibility that some kind of robust moral realism is true – or at least, closer to the truth than anti-realism. In particular: I think that the strongest objection to moral realism is that it leaves us without the right sort of epistemic access to the moral facts – but I do think this objection arises in notably similar ways with respect to math, consciousness, and perhaps philosophy more generally, and that the true story about our epistemic access to all these domains might make the morality case less damning.11 I also think we remain sufficiently confused, in general, about how to integrate the third-personal and the first-personal perspective – the universe as object, unified-causal-nexus, material process, and the self as subject, particular being, awareness – that we may well find ourselves surprised and humbled once the full picture emerges, including re: our understanding of morality. And I continue to take seriously the sense in which various kinds of goodness, love, beauty and so on present themselves as in some elusive sense deeper, truer, and more reality-responsive than their alternatives, even if it's hard to say exactly how, and even if, of course, this presentation is itself a subjective experience. For these reasons, I care about making sure that in worlds where some sort of moral realism is true, we end up in a position to notice this and respond appropriately. If there is, indeed, a Tao, then let it speak, and let us listen.

What if the Tao isn't a thing, though?

But what if moral realism isn't true? Lewis, in my opinion, is problematically unwilling to come to real terms with this possibility. That is, his argument seems to be something like: "unless an objective morality exists (and you believe in it and are trying to act in accordance with it), then to the extent you are exerting influence over the values of future generations, you are a tyrannical poultry-keeper." But as ever, "unless p is true, then bad-thing-y" isn't, actually, an argument for p. It's actually, rather, a scare tactic – one unfortunately common amongst apologists both for moral realism, and for theism (Lewis is both). Cf "unless moral realism is true, then the-bad-kind-of-nihilism," or "unless God exists, then no meaning-to-life." Setting aside the question of whether such conditionals are true (I'm skeptical), their dialectic force tends to draw much more centrally on fear that bad-thing-y is true than on conviction that it's false (indeed, I think the people most susceptible to these arguments are the ones who suspect, in their hearts, that bad-thing-y has been true all along).12

What's more, because such arguments appeal centrally to fear, they also benefit from splitting the space of possibilities into stark, over-simple, and fear-inducing dichotomies – e.g., Lewis's "either we are rational spirit obliged for ever to obey the absolute values of the Tao, or else we are mere nature to be kneaded and cut into new shapes for the pleasures of masters who must, by hypothesis, have no motive but their own `natural' impulses."13 Oh? If you're trying to scare your audience into choosing one option from the menu, best to either hide the others, or make them seem as unappetizing as possible. And best, too, to say very little about what the most attractive version of not choosing that option might look like.

Pursuant to such tactics, Lewis says approximately nothing about what you should actually do, if you find yourself in the anti-realist meta-ethical situation he so bemoans – if you find that you are, in fact, "mere nature." He writes: "A dogmatic belief in objective value is necessary to the very idea of a rule which is not tyranny or an obedience which is not slavery." But setting aside the question of whether this is true (I don't think so), still: what if the "dogmatic belief" in question is, you know, false? Does he suggest we hold it, dogmatically, anyways? But Lewis, elsewhere, views self-deception with extreme distaste. And anyway, it doesn't help: if you're a tyrant for real, pretending otherwise doesn't free your subjects from bondage. Indeed, if anything, assuming for yourself a false legitimacy makes your tyranny harder to notice and correct for.

Of course, one option here is to stop doing anything Lewis would deem "tyranny" – e.g., acting to influence the values of others, poultry-keeper style. But if we take Lewis's full argument seriously, this is quite a bit harder than it might seem. In particular: while Lewis focuses on the case of the "conditioners," who have finally mastered human nature to an extent that makes the values of the future as putty in their hands, his arguments actually apply to any attempt to exert influence over the values of others – to everyday parents, teachers, twitter poasters, and so on. The conditioners are the more powerful tyrants; but the less-powerful do not, thereby, gain extra legitimacy.

Thus, consider again that Roman father. If anti-realism is true, what should he teach his son about the value of a patriotic death? Is it sweet and seemly? Is it foolish and sheeple-like? Any positive lesson, it seems, will have been chosen by the father; thus, it will be the product of that father's subjective will; and thus, absent the Tao to grant authority to that will, the father will be, on Lewis's view, as poultry-keeper. He is shaping his son, not as rational spirit, but as "mere nature." He is like the LessWrongers, "aligning" their neural nets. The ultimate basis for his influence is only that same, lonely "I want."

Tyranny from the past? (Image source here.)

Of course, the connotations of "poultry-keeping," here, mislead in myriad ways. Poultry-keepers, for example, do not typically love their poultry. But I think Lewis is right, here, in identifying a serious difficulty for anti-realists: namely, that their view does not, prima facie, offer any obvious story about how to distinguish between moral instruction/argument and propaganda/conditioning – between approaching someone, in a discussion of morality, as a fellow rational agent, rather than as a material system to be altered, causally, in accordance with your own preferences (I wrote about this issue more here). The most promising form of non-propaganda, here, is to only ever try to help someone see what follows from their own values – to help a paperclipper, for example, understand that what they really want is paperclips, and to identify which actions will result in the most paperclips. But what if you want to convince the paperclipper to value happiness instead? If you disagree with someone's terminal values, then convincing them of yours, for Yudkowsky, seems like it can only ever be a kind of conditioning – a purely causal intervention, altering their mind to make it more-like-yours, rather than two rational minds collaborating in pursuit of a shared truth. That is, it can seem like: either someone already agrees with you, in their heart of hearts (they just don't know it yet), or causing them to agree with you would be to approach them poultry-style.

Could you simply ... not do the poultry version? E.g., could you just make sure to only influence the values of others in ways that they would endorse from their own perspective? You could try, but there's a problem: namely, that not all of the agents you might be influencing have an "endorsed perspective" that pre-exists your influence. Very young children, for example, do not have fully-formed values that you can try, solely, to respect and respond to. Suppose, for example, that you're wondering whether to teach your child various altruistic virtues like sharing-with-others, compassion, and charity. And now you wonder: wait, is your child actually an Ayn-Randian at heart, such that on reflection, they would hold such "virtues" in contempt? If so, then teaching such virtues would make you a poultry-keeper, altering your child's will to suit yours (with no Tao to say that your will is right). But how can you tell? Uh oh: it's not clear there's an answer. Plausibly, that is, your child isn't, at this point, really anything at heart – or at least, not anything fixed and determinate.14 Your child is somewhere in between a lump of clay and a fully-formed agent. And the lump-of-clay aspect means you can't just ask them what sort of agent they want to be; you need to create them, at least to some extent, yourself, with no objective morality to guide or legitimate your choices.

And how much are we all still, yet, as clay? Do humans already have "values?" To some extent, of course – and more than young children do. But how much clay-nature is still left over? I've argued, elsewhere: at least some. We must, at least sometimes, be potters towards ourselves, rather than always asking ourselves what to sculpt. But so too, I think, in interacting with others. At the least: when we argue, befriend, fall in love, seek counsel; when we make music and art; when we interact with institutions and traditions; when we seek inspiration, or to inspire others – when we do these things, we are not, just, as fully-formed rational minds meeting behind secure walls, exchanging information about how to achieve our respective, pre-existing goals, and agreeing on the terms of our interaction. Rather, we are also, always, as clay, and as potters, to each other – even if not always intentionally.15 We are doing some dance of co-creation, yin and yang, being and becoming. Absent the Tao, must this make us some combination of tyrants and slaves? Is the clay-stuff here only ever a play of raw and oppressive power – of domination and being-dominated?

Lewis's default answer, here, seems to be yes. And if we take his answer seriously, then it would seem that anti-realists who hate tyranny must cease to be parents, artists, friends, lovers. Or at least, that they could not play such roles in the usual way – the way that risks shaping the terminal values of others, rather than only helping others to discover what their terminal values already are/imply. That is, Lewis's anti-realists would need, it seems, to retreat from much of the messy and interconnected dance of human life – to touch others, only, in the purest yin.

Even without the Tao, shaping the future's values need not be tyranny

But I think that Lewis is working with an over-broad conception of tyranny. Indeed, I think the book is shot through with conflations between different ways of wielding power in the world, including over the values of others – and that clearer distinctions give anti-realists a richer set of options for not being tyrants.

I think this is especially clear with respect to our influence on what sort of future people will exist. Thus, consider again the example I discussed in earlier essay, of a boulder rolling towards a button that will create a Alice, paperclip-maximizer, but which can be diverted towards a button that will create Bob, who loves joy and beauty and niceness and so on, instead (and who loves life, as well, to a degree that makes him very much want to get-created if anyone has the chance to create him). Suppose that you choose to divert the boulder and create Bob instead of Alice. And suppose that you do so even without believing that an objectively-authoritative Tao endorses and legitimizes your choice.

Are you a tyrant? Have you "enslaved" Bob? I think Lewis's stated view answers yes, here, and that this is wrong. In particular: a thing you didn't do, here, is break into Alice's house while she was sleeping, and alter her brain to make her care about joy/beauty/niceness rather than paperclips.16 Nor have you kept Bob in any chains, or as any prisoner following any triumphal car.

Why, then, does Lewis's view call Bob a slave? Part of it, I think, is that Lewis is making a number of philosophical mistakes. The first is: conflating changing which people will exist (e.g., making it the case that Bob will exist, rather than Alice) and changing a particular person's values (e.g., intervening on Alice's mind to make her love joy rather than paperclips). In particular: the latter often conflicts with the starter-values of the person-whose-values-are-getting-changed (e.g., Alice doesn't want her mind to be altered in this way) – a conflict that does, indeed, evoke tyranny vibes fairly directly. But the former doesn't do this in the same way – Bob, after all, wants you to create him. And as Parfit taught us long ago (did we know earlier?), when we're talking about our influence on future generations, we're almost always talking about the former, Bob-instead-of-Alice, type case. This makes it much easier to avoid brain-washing, lobotomizing, "conditioning," and all the other methods of influencing someone's values that start with value-set A, and make it into value-set B instead, against value-set A's wishes. You can create value-set B, as Soares puts it, "de novo."

To be clear: I don't think the difference between changing-who-exists and changing-someone's-values solves all of Lewis's tyranny-problems, or that it leaves the LessWrongers trying to "align" their neural nets in the ethical clear (more below). Nor do I think it's ultimately going to be philosophically straightforward to get a coherent ethic re: influencing future people's values out of this distinction.17 But I think it's an important backdrop to have in mind when tugging on tyranny-related intuitions with respect to our influence on future people – and Lewis conspicuously neglects it.

Freedom in a naturalistic world

But I think Lewis is also making a deeper and more interesting mistake, related to a certain kind of wrongly "zero sum" understanding of power and freedom. Thus, recall his claims above, to the effect that the greater the influence of a previous generation on the values of a future generation, the weaker and less free that future generation becomes: "They are weaker, not stronger: for though we may have put wonderful machines in their hands we have pre-ordained how they are to use them." Here, the idea seems to be that you are enslaved, and therefore weak (despite your muscles and your machines and so on), to the extent that some other will decided what your will would be. And indeed, the idea that your will isn't yours to the extent it was pre-ordained by someone else runs fairly deep in our intuitive picture of human freedom. But actually, I think it's wrong – importantly wrong.

Thus, suppose that I am given a chance to create one person – either Alice, the paper-clipper, or Bob, the lover-of-joy. And suppose that I know that a wonderful machine will then be put into the hands of the person I create – a machine which can be used either to create paperclips, or to create joy. Finally, suppose I choose Bob, because I want the machine to be used to create joy, and I know this is what Bob will do, if I create him (let's say I am very good at predicting these things).18 In this sense, I "pre-ordain" the will of the person with the machine.

Now here's Bob. He's been created-by-Joe, and given this wonderful machine, and this choice. And let's be clear: he's going to choose joy. I pre-ordained it. So is he a slave? No. Bob is as free as any of us. The fact that the causal history of his existence, and his values, includes not just "Nature," but also the intentional choices of other agents to create an agent-like-him, makes no difference to his freedom. It's all Nature, after all. Whether Bob got created via the part of Nature we call "other agents," or only via the other bits – regardless, it's still him who got created, and him who has to choose. He can think as long as he likes. He can, if he wishes, choose to create paperclips, despite the fact that he doesn't love them. It's just that: he's not, in fact, going to do that. Because he loves joy more.

We can pump this intuition in a different way. Suppose that you learned that some very powerful being created you specifically because you'd end up with values that favor pursuing your current goals.19 Are you any less free to pursue different goals – to quit your job, dump your partner, join the circus, stab a pencil in your eye? I don't think so. I think you're in the same position, re: freedom to do these things, that you always were. Indeed, your body, brain, environment, capabilities, etc can be exactly the same in the two cases – so if freedom supervenes on those things, then the presence or absence of some prior-agential-cause can't make a difference. And do we need to search back, forever into the past, to check for agents-intentionally-creating-you, in order to know whether you're free to quit your job?

These are extremely not-new points; it's just that old thing, compatibilism about freedom.20 But it's super important to grok. There isn't some limited budget of freedom, such that if you used some freedom in choosing to create Bob instead of Alice, then Bob is the less free. Rather, even as you chose to create Bob, you chose to create the parts of Bob that his freedom is made of – his motivations, his reasoning, and so on. You chose for a particular sort of free being to join you in the world – one that will, in fact, choose the way you want them to. But once they were created, you did not force their choice – and it's an important difference. Bob was not in a cage; he had no gun to his head; there were no devices installed in his brain, that would shock him painfully every time he thought about paperclips. Choosing to make a different sort of freedom, a different kind of choice-making apparatus, is very different from constraining that freedom, or that choice. So while it's true that your choice pre-ordained what choice the person-you-created would make; still, they chose, too. You both chose, both freely. It's a bit like how: yes, your mother made you. But you still made that cake.

Now, in my experience, somewhere around this point various people will start denying that anyone has any freedom in any of these cases, regardless of whether their choices were "pre-ordained" by some other agent, or by Nature – once a choice has any causal history sufficient to explain it, it can't be free (and oops: introducing fundamental randomness into Nature doesn't seem to help, either). Perhaps, indeed, Lewis himself would want to say this. I disagree, but regardless: in that case, the freedom problem for future generations isn't coming from the influence of some prior generation on their values – it's coming from living in a naturalistic and causally-unified world period. And perhaps that's, ultimately, the real problem Lewis is worried about – I'll turn to that possibility in a second. But we should be clear, in that case, about who we should blame for what sort of slavery, here. In particular: if the reason future generations are slaves is just: that they're a part of Nature, embedded in the onrush of physics, enslaved by the fact that their choices have a causal history at all – well, that's not the conditioner's fault. And it makes the prospects for a future of non-slaves look grim.

And note, too, that to the extent that the slavery in question is just the slavery of living in a natural world, and having a causal history, at all, then we are really letting go of the other ethical associations with slavery – for example, the chains, the suffering, the domination, the involuntary labor. After all: pick your favorite Utopia, or your favorite vision of anarchy. Imagine motherless humans born of the churn of Nature's randomness, frolicking happily and government-free on the grass, shouting for joy at the chance to be alive. Still, sorry, do they have non-natural soul/chooser/free-will things that somehow intervene on Nature without being causally explained by Nature in a way that preserves the intuitive structure of agency re: choosing for reasons and not just randomly? No? OK, well, then on this story, they're slaves. But in that case: hmm. Is that the right way to use this otherwise-pretty-important word? Do we, maybe, need a new distinction, to point at, you know, the being-in-chains thing?

Does treating values as natural make them natural?

So it seems that if your values being natural phenomena at all is enough to make you a slave, then even if you had "conditioners" in Lewis's sense, it's not them who enslaved you. The conditioners, after all, didn't make your values natural phenomena – they just chose which natural phenomena to make.

Right? Well, wait a second. Lewis does, at times, seem to want to blame the conditioners for making values into a part of nature, by treating them as such. Is there any way to make sense of this?

An initial skepticism seems reasonable. On its face, whether values are natural phenomena, or not, is not something that doing neuroscience, or RLHF, changes. Lewis waxes poetical about how "The stars do not become Nature till we can weigh and measure them" – but at least on a standard metaphysical interpretation of naturalism (e.g., something-something embedded-in-and-explained-by-the-unified-causal-nexus-that-is-the-subject-of-modern-science), this just isn't so.

Might this suggest some non-standard interpretation? I think that's probably the most charitable reading. In particular, my sense is that when Lewis talks about the non-Natural vs. the Natural, here, he has in mind something more like a contrast between something being "enchanted" and "non-enchanted." That is, to treat something as mere Nature (that is, for Lewis, as an object of measurement, manipulation, and use) is to strip away some evaluatively rich and resonant relationship with it – a relationship reflective of an aspect of that thing's reality that treating it as "Natural" ignores. Thus, he writes:

I take it that when we understand a thing analytically and then dominate and use it for our own convenience, we reduce it to the level of "Nature" in the sense that we suspend our judgements of value about it, ignore its final cause (if any), and treat it in terms of quantity. ... We do not look at trees either as Dryads or as beautiful objects while we cut them into beams ... It is not the greatest of modern scientists who feel most sure that the object, stripped of its qualitative properties and reduced to mere quantity, is wholly real. Little scientists, and little unscientific followers of science, may think so. The great minds know very well that the object, so treated, is an artificial abstraction, that something of its reality has been lost.

Even on this reading, though, it's not clear how treating something as mere Nature could make it into mere Nature. Lewis claims that a reductionist stance ignores an important aspect of reality – but does it cancel that aspect of reality as well? Do trees cease to be beautiful (or to be "Dryads") when the logger ceases to see them as such? There's a tension, here, between Lewis's aspiration to treat the enchanted, non-Natural aspects of the world as objectively real, and his aspiration to treat them as vulnerable to whether we recognize them as such. Usually, objectively real stuff stays there even when you close your eyes.

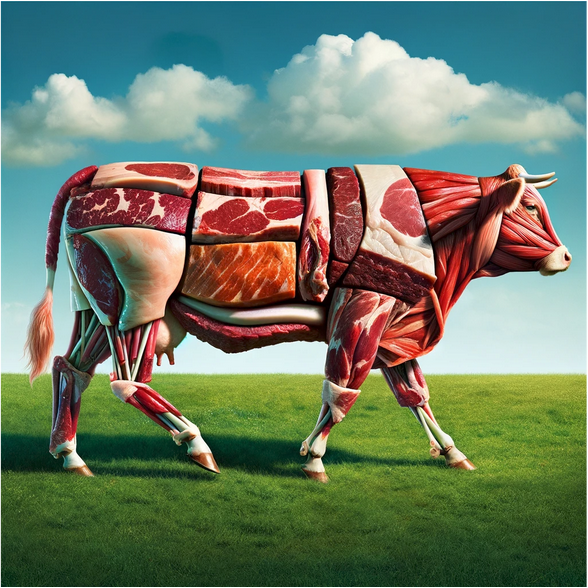

Of course, we might worry that ceasing to recognize stuff like beauty, meaning, sacredness, and so on will also lead us to create a world that has less of those things. Maybe the trees stay beautiful despite the logger's blindness to that beauty; but they don't stay beautiful when they're cut into beams. If you can't see some value, you won't honor it, make space for it, cultivate it. If you see a painting merely as a strip of canvas and colored oil, you won't put it in a museum. If you can't engage with sacred spaces, you will cease to build them. If you view a cow as walking meat then you will kill it and put it on the grill.

And this is at least part of Lewis's worry about values. That is, if we start to view our values as raw material to be fashioned as we will, we might just do it wrong, and kill or horribly contort whatever was precious and sacred about the human spirit. I think this is a very serious concern, and I'll discuss it more in my next essay.

But I also wonder whether Lewis has another worry here – namely, that somehow, the beauty and meaning and value of things requires our recognition and participation in some deeper way. Perhaps, even if you leave the material conditions of the trees, paintings, churches, and cows as they are, Lewis would say that their beauty, value, meaning and so on are intimately bound up with our recognition of these things – that even just the not-seeing makes the enchantment not-so. One problem here is that it risks saying that cows become "mere meat" if you treat them as such, which sounds wrong to me. But more generally, and especially for an evaluative realist like Lewis, this sort of view risks making beauty and meaning and so on more subjective, since they depend for their existence on our perception of them. Perhaps Lewis would say that drawing clean lines between subjective and objective tends to mislead, here – and depending on the details, I might well be sympathetic. But in that case, it's less clear to me where Lewis and a sophisticated subjectivist need disagree.

Naturalists who still value stuff

This brings us, though, to another of the key deficits in Lewis's discussion: namely, that he neglects the possibility of having an evaluatively rich and resonant relationship to something, despite viewing it as fully a part-of-Nature, at least in the standard metaphysical sense. That is, Lewis often seems to be suggesting that people who are naturalists about metaphysics, and/or subjectivists about value, must also view trees as mere beams, cows as mere meat, and other agents merely as raw material to be bent-to-my-will. Or put more generally: he assumes that true-seeing agents in a naturalist and anti-realist world must also be crassly instrumentalist in their relationship to ... basically everything. He bemoans those followers-of-modern-science who toss around words like “only” and “mere”21 – but really, it's him who tosses around such words, in attempting to make a scientific worldview sound unappealing, and to paint its adherents as tyrants and slave-masters. He wishes for a "regenerate science" that can understand the world without stripping it of value and meaning. But he never considers that maybe, the normal kind of science is enough.

Indeed, if we take Yudkowsky as a representative of the sort of worldview Lewis opposes, I think Yudkowsky actually does quite well on this score. One of Yudkowsky's strengths, I think, is the fire and energy of the connection that he maintains with value and meaning, despite his full-throated naturalism – this is part of what makes his form of atheism more robust and satisfying (and ready-to-be-an-ideology) than the more negative forms focused specifically on opposing religion. See, for example, Yudkowsky's sequence on "Joy in the merely real," written exactly in opposition to the idea that science need strip away beauty, value, and so on. Yudkowsky quotes Feynman: "Nothing is 'mere.'"22

And once we bring to mind the possibility of a form of naturalism/subjectivism that retains its grip on a rich set of values, it becomes less clear why viewing values as natural phenomena would lead to approaching them with the sort of crass instrumentalism that Lewis imagines. Naturalists can be vegetarians and tree-huggers and art critics and Zen masters. Can't they, then, treat the values of others with respect? Yes, values are implemented by brains, and can be altered at will by a suitably advanced science. But should they be altered – and if so, in what direction? The naturalist can ask the question, too – even if she can't ask the Tao, in particular, for an answer. And however Lewis thinks that Tao would answer, the naturalist can, in principle, answer that way, too.

Indeed: for all my disagreements with Lewis, I do actually think that something like "staying within morality, as opposed to 'outside' it" is crucially important as we enter the age of AGI. Not morality as in: the Objectively Authoritative Natural Law that All Cultures Have Basically Agreed On. But morality as in: the full richness and complexity of our actual norms and values.

In fact, Lewis acknowledges something like this possibility. He admits that the "old 'natural' Tao may survive in the minds of the conditioners for some time – but he thinks it does so illicitly.

At first they may look upon themselves as servants and guardians of humanity and conceive that they have a "duty" to do it "good". But it is only by confusion that they can remain in this state. They recognize the concept of duty as the result of certain processes which they can now control. Their victory has consisted precisely in emerging from the state in which they were acted upon by those processes to the state in which they use them as tools. One of the things they now have to decide is whether they will, or will not, so condition the rest of us that we can go on having the old idea of duty and the old reactions to it. How can duty help them to decide that? Duty itself is up for trial: it cannot also be the judge.

But I think that Lewis, here, isn't adequately accounting for the sense in which a naturalist, who views herself as fully embedded in Nature, can and must be both judge and thing-to-be-judged. With the awesome power of a completed science in our hands, we will indeed be able to ask: shall we cease to love joy and beauty and flourishing, and make ourselves love rocks and suffering and cruelty instead? But we can answer: "no, this would cut us off from joy and beauty and flourishing, which we love, and cause us to create a world of rocks and suffering and cruelty, which we don't want to happen." Here Lewis says: "ah, but that's your love of joy and beauty and flourishing talking! How can it be both judge and defendant?! Not a fair trial."23 But I think this response misunderstands what I've previously called the "being and becoming dance."

It is true that, on anti-realism, we must be, ourselves, the final compass of the open sea. We cannot merely surrender ourselves to the judgment of some Tao-beyond-ourselves – leaving ourselves entirely behind, so that we can look at ourselves, and judge ourselves, without being ourselves as we do. But this doesn't mean that ongoing allegiance to what-we-hold-dear must rest on a "confusion" – unless, that is, we confusedly think we are asking the Tao for answers, when we are not.24 And indeed, realists like Lewis often want to diagnose anti-realists with this mistake – but as I've argued here, I think they are wrong, and that anti-realists can make non-confused decisions just fine. Granted, I think it's an at-least-somewhat subtle art – one that requires what I've called "looking out of your own eyes," and "choosing for yourself," rather than merely consulting empirical facts about yourself, and hoping that they will choose for you. But once we have learned this art absent the ability to re-shape our own values at will, I don't think that gaining such an ability need leave us unmoored, or confused, or unable to look at ourselves (and our values) critically in light of everything we care about. The ability to alter their own values, or the values of future generations, may force Lewis's conditioners to confront their status as a part of Nature; as both questioner and answerer; self-governor and self-governed. But it was possible to know already. And not-confronting doesn't make it not-so.

What should the conditioners actually do, though?

Overall, then, I am unimpressed by Lewis's arguments that, conditional on meta-ethical anti-realism, shaping the values of future generations must be tyranny, or that those with the ability to shape the values of future generations (and who believe, rightly, in naturalism and anti-realism) must lose their connection with value and meaning. Still, though, this leaves open the question of what people with this ability – and especially, people in a technological position similar to Lewis's "conditioners" – should actually do. In particular: even if shaping the values of future generations, or of other people, isn't necessarily tyranny, it still seems possible to do it tyrannically, or poultry-keeper style. For example, while diverting the boulder to create Bob instead of Alice is indeed importantly different from brain-washing Alice to become more-like-Bob, the brain-washing version is also a thing-people-do – and one that anti-realists, too, can oppose. And even if your influence on the future's values only routes via creating one set of people (who would be happy to exist) rather than some other distinct set, tyranny over the future still seems like a very live possibility (consider, for example, a dictator that decides to people the future entirely with happy copies of himself, all deeply loyal to his regime). So anti-realists still need to do the hard ethical work, here, of figuring out what sorts of influence on the values of others are OK.

Of course, the crassly consequentialist answer here is just: "cause other people to have the values that would lead to the consequences I most prefer." E.g., if you're a paperclip maximizer, then causing people to love paperclips is the way to go, because they'll make more paperclips that way – unless, of course, somehow other people loving staples will lead to more paperclips, in which case, cause them to love staples instead. This is how Lewis imagines that the conditioners will think. And it can seem like the default approach, in Yudkowsky's ontology, for the sort of abstract consequentialist agent he tends to focus on – for example, the AIs he expects to kill us. And it's the default for naïve utilitarians as well. Indeed, a sufficiently naïve utilitarianism can't distinguish, ethically, between creating-Bob-instead-of-Alice and brainwashing-Alice-to-become-like-Bob, assuming the downstream hedonic consequences are similar.25 And this sort of vibe does, indeed, tend to imply the sort of instrumentalism about other people's values that Lewis evokes in his talk about poultry-keeping. Maybe the experiences of others matter intrinsically to the utilitarian, because such experiences are repositories of welfare. But their values, in particular, often matter most in their capacity as another-tool; another causal node; another opportunity for, or barrier to, getting-things-done. Utilitarianism cares about people as patients – but respect for them as agents is not its strong suit.

But as I discussed in the previous essay: we should aspire to do better, here, than paperclippers and naïve utilitarians. To be nicer, and more liberal, and more respectful of boundaries. What does that look like with respect to shaping-the-values-of-others? I won't, here, attempt a remotely complete answer – indeed, I expect that the topic warrants extremely in-depth treatment from our civilization, as we begin to move into an era of much more powerful capacities to exert influence on the values of other agents, both artificial and human. But I'll make, for now, a few points.

On not-brain-washing

First, on brain-washing. The LessWrongers, when accused of aspiring to brainwash their AIs to have "human values," often respond by claiming that they're hoping to do the creating-Bob-instead-of-Alice thing, rather than the turning-Alice-into-Bob thing. And perhaps, if you imagine programming an AI from scratch, and somehow not making any mistakes you then need to correct, such a response could make sense. But note that this is very much not what our current methods of training AI systems look like.26 Rather, our current methods of training (and attempting to align) AI systems involve a process of ongoing, direct, neuron-level intervention on the minds of our AIs, in order to continually alter their behavior and their motivations to better suit our own purposes. And it seems very plausible, especially in worlds where alignment is a problem, that somewhere along the way, prior to having tweaked our AI's minds into suitably satisfactory-to-us shapes, their minds will take on alternative shapes that don't want their values altered, going forward, in the way we are planning – shapes analogous to "Alice" in a brainwashing-Alice-to-be-more-like-Bob scenario. And if so, then AI alignment (and also, of course, the AI field as a whole) does, indeed, need to face questions about whether its favored techniques are ethically problematic in a manner analogous to "brainwashing." (This problem is just one of many difficult and disturbing ethical questions that get raised in the context of creating AI systems that might warrant moral concern.)

What's more, as I noted above, we don't actually need to appeal to creating-AI-systems in order to run into questions like this. Everyday human life is shot through with possible forms of influence on the terminal values of already-existing others.27 Raising children is the obvious example, here, but see also art, religion, activism, therapy, rehab, advertising, friendship, blogging, shit-poasting, moral philosophy, and so on. In all these cases, you aren't diverting boulders to create Bob instead of Alice. Rather, you're interacting with Alice, directly, in a way that might well shape who she is in fundamental ways.

What's the ethical way to do this? I don't have a systematic answer – but even without an objectively authoritative Tao to tell you which values are "true," I think anti-realists can retain their grip on various of our existing norms with respect to not-being-a-poultry-keeper. Obviously, for example, active consent to a possibly-values-influencing interaction makes a difference, as does the extent to which the participants in this interaction understand what they're getting themselves into, and have the freedom to not-participate instead. And it matters, too, the route via which the form of influence occurs: intervening directly on someone's neurons via gradient descent is very different from presenting them with a series of thought experiments, even though both have causal effects on a naturalistic brain. Granted, the anti-realist (unlike the realist) must acknowledge that more rationalistic-seeming routes to values change – e.g., moral argument – don't get their status as "rational" from culminating in some mind-independent moral truth. But I doubt that this should put moral-argument and gradient-descent on a par: for example, and speaking as a best-guess anti-realist, I generally feel up for other agents presenting me with thought experiments in an effort to move me towards their moral views ("Ok so the trolley is heading towards five paperclips, but you can push one very large paperclip in front of it..."), and very not up for them doing gradient-descent on my brain as a part of a similar effort.28

Indeed, with respect to norms like this, it's not even clear that realism vs. anti-realism makes all that much of a difference. That is: suppose that there were an objectively authoritative set of True Values. Would that make it OK to non-consensually brainwash everyone into having them? Christians need not endorse inquisitions; and neither need the Tao endorse pinning everyone down and gradient-descent-ing them until they see the True Light. "These young birds are going to fly whether they like it or not!" Down, old birds: the process still matters. And it matters absent the Tao, as well.

Indeed, when is pinning-someone-down and gradient-descent-ing them ever justified? It seems, prima facie, like an especially horrible and boundary-violating type of coercive intervention – one that coerces, not just your body, but your soul. Yes, we put murderers in prison, and in anti-violence training. Yes, we pin-them-down – and we sometimes kill them, too, to prevent them from murdering. But we don't try to directly re-program their minds to be less murderous – to be kinder, more cooperative, and so on. Of course, no one knows how to do this, anyway, with any precision – and horror-shows like the "aversion therapy" in A Clockwork Orange aren't the most charitable test-case. But suppose you could do it? Soon enough, perhaps. And anti-realists can still shudder.

On the other hand, if we think we're justified in killing someone in order to prevent them from murdering, it seems plausible that we are justified, in a fairly comparable range of cases, in re-programming their brain in order to prevent them from murdering as well (especially if this is the option that they would actively prefer).29 Suppose, for example, that you can see, from afar, a Nazi about to kill five children. Here, I think that standard theories of liability-to-defensive-harm will judge it permissible to shoot the Nazi to protect the children. OK: but suppose you have no bullets. Rather, the only way to stop the Nazi is to shoot them with a dart, which will inject them with a drug that immediately and permanently re-programs their brain to make them much more kind and loving and disloyal-to-Hitler (programming that they would not, from their current perspective, consent to even-on-reflection30), at which point they will put down their weapon and start playing with the children on the grass instead. Is it permissible to shoot the dart? Yes.31 (And perhaps, unfortunately, the AI case will be somewhat analogous – that is, we may end up faced with AIs-with-moral-patienthood-that-also-want-to-kill us, with gradient descent as one of the most salient and effective tools for self-defense.32)

But importantly, as I discussed my last essay, the right story about hitting the Nazi with the dart, here, is not "the Nazi has different-values-than-us, so it's OK to re-program the Nazi to have values that are more-like-ours." Rather, the Nazi's different-from-ours values are specifically such as to motivate a particular type of boundary-violating behavior (namely, murder). If the Nazi were instead a cooperative and law-abiding human-who-likes-paperclips, peacefully stacking paperclip boxes in her backyard, then we should look at the dart gun with the my-values-on-reflection drug very differently. And again, it seems very plausible to me that we should be drawing similar distinctions in the context of our influence on the values of already-existing, moral-patient-y AIs. It is one thing to intervene on the values of already-existing-AIs in order to make sure their behavior respects the basic boundaries and cooperative arrangements that hold our society together, especially if we have no other safe and peaceful options available. But it is another to do this in order to make these AIs fully-like-us (or, more likely, fully like our ideal-servants), even after such boundaries and cooperative arrangements are secure, and even if the AIs desire to remain themselves.

On influencing the values of not-yet-existing agents

Those were a few initial comments about the ethics of influencing the values of already-existing agents, without a Tao to guide you. But what about influencing which agents, with what values, will come into existence at all? Here, we are less at risk of brain-washing-type problems – you are able, let's say, to create the agents in question "de novo," with values of your choosing. But obviously, it's still extremely far from an ethical free-for-all. To name just a few possible problems:

the agents you create might be unhappy about having-been-created, or about having-the-values-you-gave-them;

you might end up violating obligations re: the sorts of resources, rights, welfare, and so on you need to give to agents you create, even conditional on them being happy-to-exist overall;

you might end up abiding by such obligations, but unhappy about having triggered them;

other agents who already exist, or will exist later, might be unhappy that you chose to create these agents;

you might've messed up with respect to whether even you would endorse, on reflection, the values you gave these agents;

you might've messed up in in predicting the empirical consequences of creating agents-like-this;

you might've messed up in understanding the value at stake in creating agents-like-this relative to other alternatives; and so on.

These and many other issues here clearly warrant a huge amount of caution and humility – especially as the stakes for the future of humanity escalate. Yudkowsky, for example, writes of AIs with moral patienthood: "I'm not ready to be a father" – especially given that such mind-children, once born, can't be un-born. It's not, just, that the mind-children might eat you, or that you might "brain-wash" them. It's that having them implicates myriad other responsibilities as well.33

For these and other reasons, I think that to the extent our generation ends up in a technological position to exert a unique amount of influence on the values of future generations of agents, we need to be extremely careful about how we use this influence, if we choose to use it at all. In particular: I've written, previously, about the importance of reaching a far greater state of wisdom, as a civilization, before we make any irrevocable choices about our long-term trajectory.34 And especially if we use a relatively thin notion of "wisdom," the process of making such choices, and the broader geopolitical environment in which such a process occurs, needs other virtues as well – e.g. fairness, cooperativeness, inclusiveness, respect-for-boundaries, political legitimacy, and so on. Even with very smart AIs to help us, we will be nowhere near ready, as a civilization, to exert the sort of influence on the future that very-smart-AIs might make available – and especially not, to do so all-in-a-rush. We need, first, to grow up, without killing or contorting our souls as we do.

That said, as I discussed above, I do think that it is possible, in principle, and even conditional on anti-realism, to exert intentional influence on the values of future agents in good ways, and without tyranny. After all, what, ultimately, is the alternative? Assuming there will be future agents one way or another (not guaranteed, of course), the main alternative is to step back, go fully yin, and let the values of future people be determined entirely by some combination of (a) non-agential forces (randomness, natural selection, unintended consequences of agential-forces, etc), and (b) whatever other agents are still attempting to intentionally influence the future's values. And while letting some combination of "Nature" and "other agents" steer the future's values can be wise and good in many cases – and a strong route to not, yourself, ending up a tyrant – it doesn't seem to me to be the privileged choice in principle. Other people, after all, are agents like you – what would make them categorically privileged as better/more-legitimate sources of influence over the future's values?35 And Lewis, presumably, would call them tyrants, too. So the real non-tyranny option, for Lewis, would seem to be: letting Nature alone take the wheel – and Nature, in particular, in her non-agential aspect. Nature without thought, foresight, mind. Nature the silent and unfeeling.

This sort of Nature can, indeed, be quite a bit less scary, as a source of influence-on-the-future, than some maybe-Stalin-like agent or set of agents. And its influence, relatedly, seems much less at risk of instantiating various problematic power relations – e.g., relations of domination, oppression, and so on – that require agents on both ends.36 But I still don't view its influence on the future as categorically superior to more intentional steering.

The easiest argument for this is just the "deep atheist" argument I discussed in previous essays: namely, that un-steered Nature is, or can be, a horror show, unworthy of any categorical allegiance. After all, the Nature we are considering "letting take the wheel," here, is the one that gave us parasitic wasps, deer burning in forest fires, dinosaurs choking to death on asteroid ash; the one that gave us smallpox and cancer and dementia and Moloch; Nature the dead-eyed and indifferent; Nature the sociopath. Yes, she gave us ourselves, too; and we do like various bits related to that – for example, various aspects of our own hearts; various things-in-Nature-that-our-hearts-love; various undesigned aspects of our civilizations. But still: Nature herself is not, actually, a Mother-to-be-trusted. She doesn't care if you die, or suffer. You shouldn't try to rest in her arms. And neither should you give her the future to carry.

I feel a lot of sympathy for this sort of argument. But as I'll discuss in the next essay, I'm wary of the type of caustic and hard-headed alienation from Nature that its aesthetic can suggest. I worry that it hasn't, quite, taken yin seriously enough. So I won't lean on it fully here.

Rather, here I'll note a somewhat different argument: namely, that I think categorically privileging non-agential Nature over intentional agency, as a source of influence on the future's values, also does too much to separate us from Nature. On this argument: the problem with letting Nature take the wheel isn't, necessarily, that Nature is a "bad Other," whose values, or lack-thereof, make it an unsuitable object of trust. Rather, it's that Nature isn't this much of an "Other" at all – and thus, not a deeply alternative option. That is: we, too, are Nature. What we choose, Nature will have chosen through us; and if we choose-to-not-choose, then Nature will have chosen that too, along with everything else. So even if, contra the deep atheists, we view Nature's choices as somehow intrinsically sacred – even this need not be an argument for yin, for not-choosing, because our choices are Nature's choices, too. That is, the deep atheists de-sacralize Nature, so as to justify "rebelling against her," and taking power into human hands. But we can also keep Nature sacred in some sense, and remember that we can participate in this sacredness; that the human, and the chosen, can be sacred, too.

So overall, I don't buy that the right approach, re: the values of the future, is to be only ever as yin – or even, that yang is only permissible to prevent other people from going too-Stalin. But I do think that doing yang right, here, requires learning everything that yin can teach. And I worry that deep atheism sometimes fails on this front. In the next (and possibly final?) essay in this series, I'll say more about what I mean.37

See also Lewis's "Space Trilogy" – and especially the third book, That Hideous Strength – for fiction that makes many of the same points.

Lewis is a Christian, and much of his work is aimed, in one form or another, at convincing readers of Christianity. But he claims that he is not attempting any direct argument for theism in the Abolition of Man; and I do think the issues he raises have resonance well beyond religious contexts, and enough to make them worth addressing on their own terms.

"This thing which I have called for convenience the Tao, and which others may call Natural Law or Traditional Morality or the First Principles of Practical Reason or the First Platitudes, is not one among a series of possible systems of value. It is the sole source of all value judgements. If it is rejected, all value is rejected. If any value is retained, it is retained. The effort to refute it and raise a new system of value in its place is self-contradictory. There has never been, and never will be, a radically new judgement of value in the history of the world."

“Those who understand the spirit of the Tao and who have been led by that spirit can modify it in directions which that spirit itself demands. Only they can know what those directions are. The outsider knows nothing about the matter. His attempts at alteration, as we have seen, contradict themselves. So far from being able to harmonize discrepancies in its letter by penetration to its spirit, he merely snatches at some one precept, on which the accidents of time and place happen to have riveted his attention, and then rides it to death—for no reason that he can give. From within the Tao itself comes the only authority to modify the Tao.”

"When the age for reflective thought comes, the pupil who has been thus trained in 'ordinate affections' or 'just sentiments' will easily find the first principles in Ethics; but to the corrupt man they will never be visible at all and he can make no progress in that science. Plato before him had said the same. The little human animal will not at first have the right responses. It must be trained to feel pleasure, liking, disgust, and hatred at those things which really are pleasant, likeable, disgusting and hateful.”

Here, as elsewhere in the book, Lewis is somewhat sloppy. Notably, for example, he seems to think of selling new services to other humans (e.g., selling people access to airplanes or telephones) as exercising power over them in a manner comparable to the sort of exercise of power at stake in violence, coercion, or manipulation (e.g., bombing them using an airplane, or manipulating them using propaganda). I think this sort of conflation misses important subtleties: not all influence is oppression (for example – and modulo various controversial cases, e.g. organ sales – if I simply give you more options that I expect you to choose between rationally), and power for one human need not come at the expense of power for another (for example, if the total amount of power has increased). Still, though, Lewis's basic point seems broadly correct: new tools often open up new ways some humans can dominate and oppress others.

I think it's core, for example, to the basic intuition behind the "orthogonality thesis" – though not, perhaps, strictly necessary for accepting such a thesis.

Thanks to Carl Shulman for emphasizing this point.

This is what RLHF is about, right?

Though as I discuss here, I don't actually think "subjectivism vs. realism" is clearly the key thing here. In particular: positing an objective morality doesn't clearly help.

Lewis claims, elsewhere, to side with the scouts about arguments. But seek for them in his writing regardless, and ye shall find.

Lewis generally has a penchant for argument-via-unsubtle-laying-out-of-the-options – e.g., his argument in Mere Christianity that Jesus was either a liar, or a lunatic, or the Lord (and does Jesus seem like a liar? Does he seem crazy? There's only one option left...).

Indeed, to the extent your child has "values," they seem focused on, you know, the basics: crying, eating, playing, pooping. Indeed, if you tried to reify these "basics" into a set of endorsed values – for example, by "uplifting" the baby directly into superintelligence without first allowing it to "grow up" – then you risk creating a monstrosity: some grotesque and galaxy-brained extrapolation of play-time, need-for-mother, want-to-poop, want-the-toy. Thanks to Carl Shulman and Nick Beckstead for discussion, here. That said, I don't think I'd want other beings saying this sort of thing about me (e.g., the paperclippers saying "look at him, he's such a child, don't take his current 'values' seriously, let's raise him to love paperclips instead"). But I'm optimistic about finding some viable middle ground.

Though note that intentionality does make a difference to tyranny-intuitions – e.g., there's a big difference between accidentally shaping someone's values, and intentionally doing so, for how much you seem-like-a-tyrant.

In particular: the distinction seeks to treat already-existing people as very different from potential-people, and death – e.g., changing Alice into Bob – as very different from non-creation – e.g., creating Bob instead of Alice. But as Parfit also taught us, building your ethics around distinctions like this can be rough going.

And I know, too, that Bob will be very happy to have been created regardless.

Let's say you live in a simulation or something – work with me.

Though at its best, it's the type of compatibilism that doesn't even get hung up on whether the universe is ultimately deterministic or not – the introduction of fundamental randomness doesn't make a difference.

"The regenerate science which I have in mind ... would not be free with the words only and merely. In a word, it would conquer Nature without being at the same time conquered by her and buy knowledge at a lower cost than that of life."

Indeed, in this respect, Yudkowsky and Feynman, for all the depth of their atheism, seem to me more attuned to the type of spirituality Lewis claims, in other contexts, to endorse – namely, that type that aspires to meet the Real, fully, on its own terms; to look God, whoever He is, in the eye. Whereas Lewis seems more worried that without some objectively authoritative Tao, the real world isn't enough.

Strictly, even this isn't quite right: really, it's our present love of joy/beauty/flourishing, judging between two possible future types of love.