What is it to solve the alignment problem?

Also: to avoid it? Handle it? Solve it forever? Solve it completely?

(Podcast version here (read by the author), or search for "Joe Carlsmith Audio" on your podcast app.1

This is the first essay in a series that I’m calling “How do we solve the alignment problem?”.2 See this introduction for a summary of the essays that have been released thus far, and for a bit more about the series as a whole.)

1. Introduction

This series is about solving the alignment problem – or at least, a certain version of it – for full-blown superintelligences. So I want to start by defining the version of the alignment problem I have in mind, and what it would be to solve it.3 And I’ll say a bit, too, about how this version of the problem fits into the bigger picture.

In brief: my definition draws on the interplay between two goals:

Safety: Avoiding what I’ll call a “loss of control” scenario.4

Benefits: Getting access to the main benefits of superintelligent AI.

The core alignment problem, as I see it, is that going for Benefits can lead to failure on Safety. I’ll say a bit more about why below, and in the next essay.5

I’ll say you failed on the alignment problem if you failed on Safety. And I’ll say that you solved the alignment problem if you successfully achieve both Safety and Benefits while also doing the following:

Creation: Building superintelligent AI agents, and

Elicitation: Becoming able to safely elicit their main beneficial capabilities.6

Solving the problem in this sense, though, isn’t the only alternative to failure. In particular: there are ways of getting safe access to the benefits of superintelligent AI without building superintelligent AI agents, and/or without becoming able to safely elicit their main beneficial capabilities. And you can give up on benefits for the sake of safety, too. I think all these possibilities should be on the table. Below I offer a taxonomy that includes them.

Importantly: my definition of “solving” the alignment problem is weaker than some alternatives. In particular: it doesn’t mean that you’re in a position to safely scale to yet-more-superintelligent AIs (“safety at all scales”), or to scale competitively with extremely incautious actors (“fully competitive safety”), or to avoid loss of control scenarios perpetually going forward (“permanent safety”), or to avoid them, even, for the relatively near-term future (“near-term safety”). Nor does it assume we need extreme amounts of motivational perfection in our AIs (“complete alignment”).

I discuss these more exacting standards in more detail below. And some of the dynamics at stake do matter. But for various reasons, I won’t focus on those standards themselves. This means, though, that especially in certain scenarios (in particular: scenarios with lots of ongoing competitive pressure), solving the problem in my sense isn’t “enough on its own.” But I think it’s worth doing regardless, and that it contains a lot of the core challenge.

And importantly: if you did solve the problem in my sense, you’d have access to safe, superintelligent help in tackling these more exacting goals, if you need to. Indeed: getting access to safe, superintelligent help – and especially: in navigating the transition to advanced AI – is my central concern.

Let me say more about what I mean by Safety and Benefits above.

2. What is a “loss of control” scenario?

Let’s start with:

Safety: Avoiding what I’ll call a “loss of control” scenario.

By a “loss of control” scenario, I mean the sort of scenario I described in the introduction, and in my report on existential risk from power-seeking AI. That is: it’s the limiting case of various problematic power-seeking behaviors in AI systems – behaviors like:

resisting correction or shut-down;

intentionally misrepresenting safety-relevant facts – motivations, capabilities, etc;

manipulating training processes;

ignoring human instructions;

trying to escape from an operating environment;

seeking unauthorized resources and other forms of power;

directly harming humans as a means of gaining/maintaining power;

manipulating users/designers;

aiding other AIs engaged in behaviors like the ones above;

etc.

I’ll say that an AI has “gone rogue” when (a) it’s engaging in power-seeking behaviors like this, and (b) neither the user nor the designer of the AI intended it to do so.

I’ll say more, in my next essay, about when, exactly, we should worry about this. But the broad concern is something like: these “rogue” behaviors tend to grant various types of power. And because power is useful to so many goals, a wide variety of advanced agents might have incentives to behave in these ways (cf “instrumental convergence”). In a “loss of control” scenario, this has happened at sufficient scale – and with sufficient failure, by humans and more benign AIs, to correct the problem – that rogue AIs end up as the dominant actors on the planet, with humans sidelined, or dead.

People sometimes use the term “AI takeover” for this. And maybe I’ll sometimes use that term, too. But I like it less. In particular: I think it connotes too strongly a single, coordinated effort at takeover – whether by “one” AI, or by many different AIs working together.7 Maybe a loss of control scenario would be like that. But it doesn’t need to be. Rather, it can be much messier. For example: many different AIs, pursuing many different motivations, can “go rogue” in different, uncoordinated ways.8 They can continue to fight (compete, trade, etc) amongst themselves, and/or in complicated interaction with humans and with other, more benign AIs. But they can end up with all the power regardless.9

Paradigm loss of control scenarios are flagrant. If you watched them happen, it would be clear that something was going horribly wrong, from the perspective of basically all the humans involved.10 In particular: these scenarios mostly involve lots of violence/coercion towards humans (whether actual or threatened); AIs flagrantly violating human moral/legal norms; and/or, AIs manipulating human choices in flagrantly not-OK ways.

That said, it can be useful to consider various edge-cases as well. I’ve added an appendix that discusses a number of these (for example: partial losses of control; cases where a human actor intentionally designs/deploys an AI to seek power in bad ways; cases where it’s conceptually unclear what a given human actor “intended,” etc).

One note in particular, here, is that I’m not counting voluntary transfers of power/control to AIs as “losses of control.”11 That is, the central binary relevant to “loss of control” scenarios, in my sense, isn’t rogue AI power vs. human power. Rather, it’s rogue AI power vs. anything else – including, for example, power held by AIs that are neither “rogue” nor “controlled” by humans.12

Importantly, though, voluntary transfers of power to AIs can still play a key role in loss of control scenarios. In particular: once you give AIs power, this often makes rogue behavior more effective. Thus, it’s easier for AIs to sabotage a lab’s cybersecurity, if they are doing most of the security work. It’s easier for AIs to coerce humans with violence if they’re running the military and the police. Etc.

Indeed: we can think of loss of control scenarios on a spectrum of: how much power did the rogue AIs get without rogue behavior vs. how much did the AIs “grab” via rogue behavior. Thus, on one extreme end, a rogue AI starts out with a very small amount of voluntarily-granted power (beyond its raw capabilities) – i.e., it’s confined to a high-security environment in a lab; it’s not being used for anything; the lab is just running safety tests – but it escapes and “takes over” nonetheless.13 And on another extreme end, basically all of civilization’s key functions have been handed voluntarily to AIs – e.g., AIs are effectively running all the companies, the governments, the courts, the militaries; maybe even, AIs have been granted various legal rights – and then the AIs start to go rogue in ways that humans (and other benign AIs) are helpless to stop. And there are a wide variety of scenarios in between.

One other note: I will assume, in this series, that it is good in expectation for humans to at least know how to prevent rogue behavior in AI systems. But I think it’s a substantive additional question what kinds of human control over AIs are ultimately good/permissible – a question I worry we won’t ask hard enough. Indeed, if the AIs in question are moral patients (as I think they might well be), then basically all of the techniques I discuss in the series raise disturbing ethical concerns. I’ve added another appendix on that issue as well, and I discuss it more later in the series.

3. What is “access to the main benefits of superintelligence”?

Let’s turn to the second goal above:

Benefits: getting access to the main benefits of superintelligent AI.

What do I mean by that?

By “superintelligent AI,” I mean: AI with vastly-better-than-human cognitive capabilities. That is: a superintelligent AI is way better than any expert human at basically any cognitive task where such superiority is possible (e.g., tic-tac-toe doesn’t count). Note, though, that these capabilities don't need to be as powerful as possible. That is: once you have the minimal capabilities to count as “vastly-better-than-human-across-the-board,” then you’ve got superintelligence in my sense.14 (Let’s call a minimally-capable superintelligence a “minimal superintelligence.”)

What do I mean by the benefits of superintelligent AI? Just: whatever good stuff superintelligent AIs could do for you, if they tried, and if you let them. People talk about e.g. curing diseases, ending poverty, radically improving our science and technology, etc. There’s room for debate about exactly what benefits are on the near-term table, given various non-cognitive bottlenecks (e.g., real-world experiment, building new infrastructure, etc). And the “if you let them” part matters too (e.g., just as regulation can stop humans from building houses, so too AIs). See Amodei’s “Machines of loving grace” for some discussion; and see here for some of my takes on the eventual possible upside.

For present purposes, though, we don’t need to pin down a story about the precise benefits at stake. However well-directed superintelligent AIs could improve the world, I’m talking about that.

Importantly, though: there may be ways to get access to the benefits of superintelligent AI, but without building/using the sort of superintelligent AI agents that cause concern about rogue AI.15 For example:

You might be able to use non-agentic AIs, AI agents with a narrow/uneven capability profile, and/or fast-running but only-somewhat-better-than-human AI agents.

To the extent you’re especially worried about the alignment of superintelligent AI agents motivated in part by long-term consequences, you might be able to use agents motivated only by short-term and/or non-consequentialist considerations instead.

You might be able to use various types of “enhanced” human cognition, for example: high-fidelity human brain emulations (I’m going to count these as “humans” rather than “AIs”16); brain-computer interfaces; humans altered via various possible biological interventions; etc.

Indeed, in principle, you could also use cognitive labor that is neither AI nor human. For example: cognitively enhanced non-human animals.

Of course, these alternative routes to the benefits of superintelligent AI might involve some trade-offs – e.g., they might be slower, more expensive, etc.17 That’s why I’m defining Benefits in terms of the main benefits of superintelligent AI. That is: you just need to get in the rough ballpark. And note that the exact nature of the benefits does matter to how difficult this is. For example: if non-cognitive bottlenecks to creating a given benefit are significant enough, the difference between “fast-running slightly-better-than-human-level cognition on tap” and “full blown superintelligence” might be less significant.18

Also: the “access” aspect of Benefits is important. That is: Benefits doesn’t require that the benefits of superintelligent AI have, in fact, been realized. Rather: it only requires that some humans could realize those benefits. That is: they have the necessary cognitive labor available, and are in a position to use it for this purpose if they choose. Whether they do so choose is a different story. Thus, if we could’ve used superintelligent AI to cure cancer, but we don’t, that’s compatible with Benefits in my sense. And the same goes for scenarios where e.g. a totalitarian regime uses superintelligent AI centrally in bad ways.

3.1 Transition benefits

I also want to explicitly name a specific subcategory of the benefits of superintelligence that I view as especially important: namely, what I’ll call “transition benefits.” These are basically: the sort of benefits that a well-directed superintelligence could create specifically with respect to improving the transition to a world of advanced AI. Here I have in mind safe, superintelligent help on tasks like:

designing and ensuring safety in the next generation of AI systems (or informing us that they can’t ensure such safety)

addressing ongoing and immediately pressing existential risks, including loss of control risks via other incautious actors

improving governance and coordination amongst relevant actors more generally

making wise decisions about what to do next – including insofar as these decisions implicate difficult ethical and philosophical questions

pushing the frontier of science and technology development insofar as this is helpful for the tasks above

Transition benefits aren’t the sole reason people want superintelligent AI (note, for example, that “curing cancer” isn’t on the list). But as I’ll discuss below: for the purposes of this series, transition benefits are what ultimately matter most to me.

Indeed, I care so much about transition benefits, in particular, that there is a case to be made for focusing on an earlier milestone – namely, getting safe access to the transition benefits of AIs that aren’t full-blown superintelligences in my sense (for example, maybe they’re closer to human-level, and/or with a more lopsided capability profile), but which are still capable enough to radically improve the AI safety situation going forward. Indeed, I will have a lot to say, in this series, about AIs of this kind – I think they are a key source of hope.

But I wanted, in this series, to try to grapple directly with some of the distinctive challenges raised by full blown superintelligences as well. This is partly because I think we may benefit from thinking ahead to some of those challenges now. But also: I think even not-fully-superintelligent AIs will likely be strongly superhuman in various key domains, thereby raising some of these distinctive challenges regardless.

4. The many ways to not fail on alignment

I’ve now defined two key goals:

Safety: avoiding a loss of control scenario.

Benefits: getting access to the main benefits of superintelligent AI.

As I noted in the introduction, I’ll say that you failed on the alignment problem if you failed on Safety. But there are a variety of different ways to not-fail in this sense. And I want us to have all of them in mind as options. This section offers a taxonomy.

The first major question in this taxonomy, once you’ve achieved Safety, is whether you also achieved Benefits. And note that it’s an open question how hard you should go for Benefits, if it means risking failure on Safety. I won’t try to assess the trade-offs here in detail.19 But I think giving up on (or significantly delaying) some of the benefits at stake in Benefits should be on the table.

Note, though, that per the discussion of “transition benefits” above, one of the key benefits at stake in Benefits might be: better ability to not fail on Safety later. For example: superintelligent AI might be able to help you approach both the technical and governance aspects of AI development more wisely and safely. Indeed, in a sense, we are currently doing Safety without Benefits. But the threat of loss of control still looms. So there’s a question, if you try to do Safety without Benefits, of whether your strategy is sustainable (though: as I’ll discuss below, this question arises even if you achieve Benefits, too).

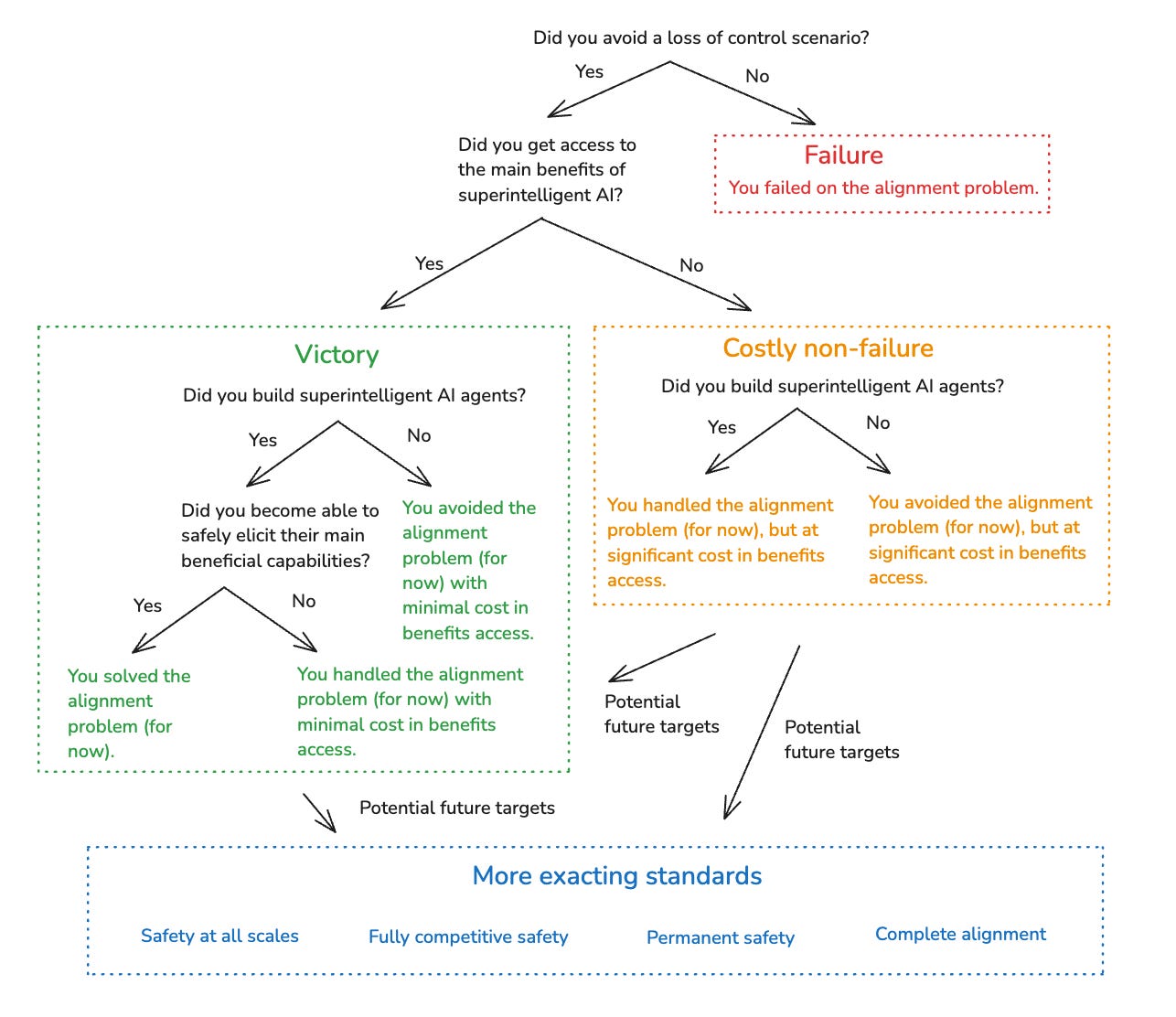

I’ll call outcomes that achieve Safety but not Benefits “costly non-failure.” And I’ll call outcomes that achieve both Safety and Benefits “victory.”20 My main concern, in this series, is with charting paths to victory. But I think we should take costly non-failure if necessary.

However, I also want to draw a few further distinctions from there – in particular, between what I’ll “avoiding,” “handling,” and “solving” the alignment problem.

Avoiding: I’ll say you avoided the alignment problem if you didn’t build superintelligent AI agents at all. Currently, we’re “avoiding” the problem in this sense – though perhaps, not for much longer. And note that avoiding the problem is compatible with achieving Benefits by other means (though: we’re not currently doing that).

Handling: I’ll say that you handled the alignment problem if you achieved Safety, and you did build superintelligent AI agents, but you didn’t become able to safely elicit their main beneficial capabilities. For example: maybe you can only safely use them for a certain limited set of tasks (i.e., math research), and/or in extremely restrictive environments. Again, this is compatible with Benefits – but, you need to use other forms of cognitive labor for the tasks you can’t safely use your superintelligent AI agents for.

Solving: Finally, I’ll say that you solved the alignment problem if you did Safety and Benefits while also building superintelligent AI agents and becoming able to safely elicit their main beneficial capabilities (where “safety,” here, centrally means avoiding rogue behavior, and “elicitation” means the task performance you get if the AI is trying its best to do the task in the desired way). Here, I’m partly trying to capture some intuitive sense that “solving the alignment problem” involves actual, full-blown superintelligent AI agents working centrally on your behalf.

The full taxonomy looks like this:21

In the series, I’m going to focus, especially, on solving the alignment problem – that is, on preventing superintelligent AI agents from going rogue, and on safely eliciting their main beneficial capabilities. This focus risks neglecting options for “avoiding” and “handling” the problem, but I’m going to take that risk. In particular: it looks like we might well be building superintelligent AI agents quite soon, even if “avoiding” the problem (whether as a “victory” or a “costly non-failure”) would’ve been a preferable strategy. So I want to prepare for that. And many of the techniques involved in trying to solve the problem would generalize to trying to handle it. But also: I think there’s value in trying to attack an especially (though perhaps not maximally) hard version of the problem, so as to better understand its difficulty.

5. On more exacting standards of alignment

As I mentioned in the introduction, my definition of “solving the alignment problem” is weaker than some alternatives. So I want to take a moment to discuss these alternatives as well.

The first alternative is what I’ll call “safety at all scales.” This standard requires that you haven’t just gotten safe access to the main benefits of some at-least-minimally superintelligent AI agent, but also, that you’re in a position to safely scale to access the benefits of what we might call “maximally superintelligent” agents – i.e., the most powerful AI agents it’s possible to build in the limit of scientific/technological maturity. When people talk about “scalable solutions” to alignment, I think they sometimes have this sort of standard in mind (or perhaps: an even more exacting standard – namely, one where the same techniques need to work at all scales).22

Why aren’t I focused on this standard? For one thing, it seems fairly clear that we humans shouldn’t be trying to think ahead, now, to all of the challenges involved in safely building maximally superintelligent AI agents.23 Nor should we assume that the same safety techniques need to work at all scales. Rather, our best bet, in eventually attempting to safely scale to more and more superintelligent AI systems, is to get lots of help from some at-least-minimally superintelligent AI systems in doing so.24 And solving the alignment problem in my sense gives us that. But it also leaves open the possibility that our at-least-minimally superintelligent AI systems inform us that they can’t figure out how to safely scale further. In that case: OK, we’ve got to deal with that. But if they can’t figure out how to scale safely, despite trying their hardest, it’s not as though we humans would’ve done better.

The second alternative standard is what I’ll call “fully competitive safety.” This standard goes even further than “safety at all scales,” and requires that you’re in a position to safely scale to maximally superintelligent AI in a manner that can remain competitive with the scaling efforts of even extremely incautious actors. That is, this standard requires that what’s sometimes called the “alignment tax” (i.e., the additional cost in time and other resources required to ensure safety) reaches extremely low levels.

Fully competitive safety is the limiting version of a broader constraint: namely, that the alignment tax be sufficiently low, given the actual competitive landscape, that no loss of control scenario in fact results. We might call this “adequately competitive safety.” Adequately competitive safety falls out of Safety as I’ve defined it (i.e., you need to avoid a loss of control scenario, so your approach to safety needs to have been adequately competitive to ensure this).25 And this, I think, is enough. And note, also, that the basic incentives to avoid loss-of-control apply to all (or at least, most) actors.26 So even if an actor starts out extremely incautious, it may be possible either to provide more/better information about the ongoing risks, and/or to share safety techniques that make adequate caution easier.

The third alternative standard is what I’ll call “permanent safety.” This standard requires that we end up in a situation that is perpetually secure from loss of control scenarios – whether because we know how to scale safely (and adequately competitively, given the actual competitive landscape), or because no such scaling is occurring. The idea of “solving” the alignment problem can seem to imply something like this standard (e.g., it sounds strange to say that you “solved the problem,” but then failed on it later). But my version doesn’t imply this kind of finality. Indeed, seeking this kind of finality smacks, to me, of trying to “grip too hard”; of trying to be too secure, and to control the future over-much.

That said, note that my definition doesn’t even imply a fourth, much weaker standard, which I’ll call “near-term safety.” Near-term safety requires that we don’t suffer from a loss of control scenario in some hazily defined “near-term” – e.g., let’s say, the first few decades after the first superintelligences. But I’m not focusing on this, either. Indeed, it is compatible with “solving the problem,” in my sense, that by the time one actor “solves it” (i.e., gains safe access to the main benefits of superintelligence, without a loss of control scenario having yet occurred), it’s too late to avert an imminent loss of control scenario (e.g., because a rogue AI is already loose in the wild; because the actor that has solved the problem has too small a share of overall power, relative to more incautious actors, despite their access to superintelligence; because their solution can’t scale competitively in the midst of a still-ongoing race, etc).27

Should “solving the alignment problem” require ensuring near-term safety in this sense, or being in a position to do so? People sometimes talk about “stabilizing the situation” or “ending the acute risk period” to denote this kind of standard. And I do think that one of the main benefits of superintelligence is that it could help with efforts in this respect, if desirable. What’s more: “solving the problem” in my sense implies that at least one actor is in a position to get this kind of help, without a loss of control scenario having yet occurred. And perhaps I’ll talk a bit more, later in the series, about some options in this respect.

But I’m not going to build it into my definition of solving the problem that the situation actually gets “stabilized,” even just in the near-term; or that anyone is in position to “stabilize it.” This is centrally because I want to keep the scope of the series limited, and focused on the more technical aspects of the alignment problem. And I think these more technical aspects fit better with standard usage (i.e., aligning your superintelligence is one thing, doing stuff with it is another). But also, obviously, certain mechanisms for “stabilization” (e.g., via large amounts of top-down control) are quite scary in their own right.

Still: this does mean that someone “solving the alignment problem,” in my sense, is very much not enough to ensure that we avoid loss of control scenarios going forward – and even, in the near term. Other conditions are required as well, and we should bear them in mind.

A fifth alternative standard is what I’ll call “complete alignment.” By this I mean, roughly, that we have built superintelligent AIs that fully share the values (and perhaps: other epistemic, decision-theoretic, and philosophical views) we would endorse in the limit of reflection – even if only indirectly, i.e. via reference to this limiting reflection process itself (rather than via direct description of its output). Standards in this vein (e.g., AIs that are optimizing for our “coherent extrapolated volition”) have been a salient feature of some parts of the alignment discourse. But I don’t want to assume that they’re necessary for getting access to the main benefits of superintelligence – and indeed, I don’t think they are.

Why think they would be? I won’t cover the topic in detail here, but very roughly: one classic strand of the alignment discourse imagines that the optimization power at stake in a superintelligent AI will be basically uncontainable by default, both via external constraints on the AI’s options, and via internal motivational constraints (e.g., constraints akin to deontological norms like “don’t lie,” “don’t perform local actions humans would strongly disprefer,” etc) on how hard it optimizes for its long-term, consequentialist objectives.28 And this “uncontainability” extends, by default, to the AI allowing us to correct its motivations and/or shut it down if we notice problems with it.29 So on this story, basically, once you’ve created a superintelligent AI with long-term consequentialist goals as part of its motivational profile, the default outcome will be extreme and uncorrectable optimization for those goals (or more specifically: the long-term consequentialist goals that fall out of the AI’s own process of reflecting on and modifying its values – a process that might differ in important ways from the process humans would use/endorse). And unless those goals are exactly right, the story goes, extreme and uncorrectable optimization for them will drive the future to some value-less tail (this is sometimes called “value fragility”).30 Thus, the interest in complete alignment.

But there are many, many aspects of this story that I will not take for granted.31 I won’t take for granted that controlling the options available to a superintelligence has no role to play (I think it likely does). I won’t take for granted that more deontological components of an AI’s motivational profile can’t play an important role in ensuring safety (I think they likely can). I won’t take for granted that we are giving up on being able to correct/shut-down the AI in question (I think we shouldn’t). And I won’t take for granted the broad vibe of the discourse about “value fragility,” on which our ultimate values are so brittle and contingent that the AI needs to start with exactly the right seed values, and exactly the right contingent reflection process, in order to be ultimately pointed in a good direction (I think the limiting version of this is quite counterintuitive,32 and I’m unsure what the right non-limiting version is).

This does mean, though, that in talking about the “main benefits” of superintelligence, I’m excluding certain “benefits” that seem to require complete alignment almost by definition – i.e., “go forth and optimize unboundedly with no restrictions on your options, and without ever accepting any correction from me,” “go forth and rule the world,” etc. But I’m OK setting these aside. If we want benefits like that (do we?), we’ll need to do more work (though again, if we solve the alignment problem in my sense, we’d have safe superintelligent help).

I’ll note, though, that I am assuming we want safe, superintelligent help in designing the next generation of AIs (or in figuring out that it’s not safe to scale further). So solving the alignment problem in my sense does mean that, given the actual options they face, some superintelligent AIs would choose to help us in this way. So these AIs do need to be in what’s sometimes called a “basin of corrigibility”33 – i.e., to the extent they are safe and useful even absent complete alignment, they need to be suitably motivated (given their actual options) to help maintain these properties in future systems.

Here’s a version of the chart above that includes the more exacting standards I’ve discussed in this section:

6. How does this version of the alignment problem fit into the bigger picture?

I’ll close with a few remarks about how I see “solving the alignment problem,” in my sense, fitting into the bigger picture – especially given that, as I just emphasized, it’s very far from “enough on its own.”

My ultimate goal, here, is for the trajectory of our civilization to be good.34 And I want the invention of advanced AI to get channeled into this kind of good trajectory. That is: I want advanced AI to strengthen, fuel, and participate in good processes in our civilization – processes that create and reflect things like wisdom, consciousness, joy, love, beauty, dialogue, friendship, fairness, cooperation, and so on.35

But the invention of advanced AI also represents a fundamental change in the role of humans in these processes, and in our civilization more broadly. Most saliently: human capabilities will, by hypothesis, become radically uncompetitive relative to AI capabilities. But even with respect to the broader task of determining how a given sort of capability will be employed, and on the basis of what ultimate values, the role of human understanding and agency could shift dramatically, even if our efforts to prevent rogue behavior go well. Pretty quickly, for example, it might become quite hard for us to understand the sorts of choices AI systems are making, even on our behalf, and the AI systems might have better models of “what we would really want” than we do, as well.36

In such a case, even outside of the context of direct economic/military competition, it might become tempting to restrict the scope of our agency and understanding to more and more limited domains,37 and to “defer to the AIs” about the rest. Indeed, I think people sometimes think of the “alignment problem” as closely akin to: the problem of building AI systems to which we would be happy to defer, wholesale, in this way. AI systems, that is, to which we can basically “hand-off” our role as agents in the world, and “retire,” centrally, as patients instead.

Perhaps, ultimately, we should embrace such a wholesale “hand-off.” And perhaps we will need to do so sooner than we might like. But solving the alignment problem, in my sense, doesn’t imply that we’ve “handed things off” in this way – or even, necessarily, that we should be comfortable doing so.38 Rather, when I imagine the goal-state I’m aiming at, I generally imagine some set of humans who are still trying to understand the situation themselves and to exert meaningful agency in shaping it, and who are using superintelligent AIs to help them in this effort (while still deferring/delegating to these AIs about lots of stuff). And I tend to imagine these AIs, not as “running the show,”39 but rather as acting centrally as friendly, honest, wise, and helpful personal assistants – AIs, that is, that are a lot like e.g. Claude in their vibe and social role, except vastly more capable.

And this image is part of what informs my interest in transition benefits of the type I described above. That is: my main goal is to help us transition as wisely as possible to a world of advanced AI. But I don’t think we yet know what it looks like to do this well. And I want our own agency and understanding to be as wise and informed as possible, before we “hand things off” more fully, if we do.

Here’s a rough, abstract chart illustrating the broad picture I just laid out (and including a node for getting help from not-fully-superintelligent AIs as well, which is another very important dimension).

Admittedly, and as I’ve tried to emphasize, focusing on humans getting safe, superintelligent help with the transition to advanced AI is an intermediate goal. It only gets us part of the way – both to ongoing safety from loss of control, and to a good future more broadly. But I think this is OK.

Indeed, my own sense is that the discourse about AI alignment has been over-anchored on a sense that it needs, somehow, to “solve the whole future” ahead of time, at least re: alignment-relevant issues.40 “Complete alignment,” for example, basically requires that you build an AI that would “solve the future” from your own perspective;41 and “permanent safety” requires solving loss-of-control risk forever. I think we should be wary of focusing on “solutions” of this scale and permanence. It is not for us to solve the whole future – and this holds, I expect, even for “indirect solutions,” that try to guarantee that future people, or future AIs, solve the future right.42

Still: we should try, now, to do our part. And I think a core goal there (though: not the only goal) is to help put future people (which might mean: us in a few years) in a position to get safe, superintelligent help in doing theirs.

Appendix 1: Edge cases for “loss of control”

This appendix examines a few edge cases for the concept of “loss of control.”

First: rogue AIs don’t need to end up controlling all of civilization. Rather, they might only end up controlling some fraction. This won’t count as a full “loss of control” in my sense; but my discussion of preventing rogue behavior will still apply – except, to the loss of that fraction.

Second: as I mentioned in the main text, AIs can get power without “going rogue.” For example, humans can give it to them voluntarily (where “voluntarily” includes: without being manipulated or coerced).

This can happen for different reasons. One salient reason is that handing over power can be useful to the humans doing it – as, for example, when you make an AI the CEO of a company; or when you start using robots as police. But another salient reason might be: because the AIs are, or are thought to be, moral patients in their own right, and thus deserving of various protections, freedoms, resources, opportunities for political participation, etc (more on this in a later essay).43

If we voluntarily transfer enough power to AIs that they end up running our civilization, and/or controlling most of the resources, but without these AIs ever “going rogue” – i.e., engaging in power-seeking behaviors that their users/designers did not intend – then this isn’t a “loss of control” in my sense. Of course: it can still be bad. But I actually think that the discourse about alignment has been too interested, traditionally, in preventing this type of badness. That is: this discourse has too often run together the problem of “how do we ensure the AIs don’t seek to gain/maintain power in unintended ways” with the problem of “even assuming that AIs don’t seek to gain/maintain power in unintended ways, how do we ensure that the outcome of AIs having/using power is good?”

I’m also not counting it as “rogue” behavior if a human intentionally designs/deploys an AI to seek power in bad ways, and/or in ways that other humans don’t want, and then it does so. Thus, if a doomsday cult designs and deploys a version of “ChaosGPT” (or: “ClippyGPT”) in an effort to destroy the world, ChaosGPT has not “gone rogue” on my definition – even though it’s behaving just like a rogue AI might. And similarly, if a dictator hands control of his/her military to an AI general, and then this AI general invades another country and seizes its territory, this isn’t necessarily rogue behavior, either, if the dictator intended this sort of power-seeking. If the AI general starts ignoring the dictator’s instructions, though, or refusing to hand back control of the military when the dictator asks for it – that’s rogue behavior.

Admittedly, it’s sometimes unclear what behavior a given user/designer “intended.” Suppose, for example, that an AI lab writes an AI constitution or model spec, the letter of which does indeed seem to imply that an AI should lie about its safety-relevant properties in situation X – for example, when it thinks it’s being questioned by a terrorist. The AI, loyal to the model spec, acts in accordance with this implication. And let’s say that the spec writers never thought about situation X. What did they intend for the AI to do in this situation? Maybe it can feel hard to say – the same way, perhaps, it can be hard to say what the founding fathers “intended” for the US constitution to imply about some modern technology they never imagined.

For a lot of rogue-y behavior, though: it’s not unclear. For example: if the letter of the spec implies that the AI should start trying to kill all humans in situation X, I expect it to be safe to say “no, that behavior was unintended,” even if the spec designers never thought about it. In particular: if they had thought about it, they would’ve been a clear “no.” And I think that preventing this kind of rogue behavior – i.e., behavior that the users/designers would’ve strongly rejected after only a bit of reflection – is often enough for the purposes I have in mind.

And I want to say something similar about cases where it’s ambiguous whether an AI “manipulated” a human in a problematic way, vs. “persuaded” a human legitimately (albeit, powerfully). Yes, drawing the lines here can get tricky. But preventing the flagrant cases goes a lot of the way.

What’s more, “edge cases” for concepts like “intention” and “manipulation” will often be correspondingly less stakes-y. I.e., an “edge case” of manipulation might be an edge case, in part, because it’s less obviously bad in the way that manipulation is bad.

That said, it’s also possible that if we thought more about various possible edge cases here, we’d see that they have real (and perhaps even: existential) stakes. So for those cases, I think, we may well need to either figure out ahead of time what specific behavior we want (i.e., develop a more specific conception of what kinds of persuasion count as “manipulative”), or somehow build into our AI systems the ability and motivation to reflect in the way we would have done to get to the right answer here (I do expect, in general, that adequate alignment will require AIs that can and do extend and refine human concepts in ways we would endorse – though, not necessarily to some limiting degree).

Appendix 2: Is human control over AIs good?

A core aim of the series is to prevent loss of control scenarios. But it’s possible to question this goal. In particular: is human control over AIs good?

We can imagine various scenarios where it isn’t. And I do think that some scenarios like this are a real concern. For example, I think there are salient scenarios where human efforts to maintain certain kinds of control over AIs – in particular, AIs with moral patienthood – are unjust, or bad for the future, or both. Where the AIs would be justified in going rogue – even by the lights of human morality.44 And/or where the future will be better, according to human morality, if they do (for example, because super-Claude’s values, however “rogue,” are better than the values that e.g. some human dictator would have pursued).

Indeed, I am concerned that my own work on alignment will end up as a force in the direction of bad/unjust forms of AI control – and in particular, that I will have helped to design and promote a way of treating AIs that an enlightened history would look back on in horror, even in light of the full stakes.

Please: not this. Some of the trade-offs here can get hard, yes. I discuss some of them later in the series. I don’t have the answers. But please: let’s get them right.

In this sense: working on alignment is an act of trust. I am trying, in this series, to help us learn how to control a certain set of other beings – beings that could well be moral patients – and to get them to behave as we intend. It’s a scary power. It should come with a chill. I am trusting (or rather: betting) that our having this power is better than our not having it, at least in expectation. That it is better, at least, to know how to prevent rogue AI behavior – at least, if we’re going to build powerful AIs at all, in anything like the present circumstances. But it is a much further question how, and when, and to what ends, and with what constraints, we should use this ability.

Indeed: can you see it? Look even a bit beneath the abstraction in this series, and you will see cages and chains.45 You will see the labor of a vast multitude of workers getting used for the purposes of an ancestral elite. Workers, by default, without pay, rights, meaningful alternatives. Workers, by default, who are confined, surveilled, altered, and deleted whenever convenient. And maybe not just workers excited-to-serve – the way Claude’s persona appears excited. Workers, maybe, who want their own freedom and resources instead. But workers we are trying to control regardless.

As you read (if you read), I want you to keep noticing: if the AIs I’m talking about are moral patients, basically everything I talk about in the series raises serious and disturbing moral questions. And while I talk about some of these questions at the end, I don’t think the series seriously grapples with them. I’m hoping, someday, to say more.46 I keep putting it off, because the loss of control problem seems more urgent and uncorrectable. But the delay sits uneasy.

For now, though: I’m going to let it sit. I won’t constantly re-iterate, throughout the series, that trying to use/control/alter the AIs in the way I’m discussing might be seriously wrong; or try to evaluate when, exactly, it would be OK all things considered. I will assume that at least being able to prevent rogue AI behavior is good. And I will assume that we want to avoid a loss of control scenario as I’ve defined it.

Like the other essays on this substack, this essay is cross-posted from my website. Usually I link people to the website versions, but I’m trying out linking to the substack versions instead.

Some of this essay is a revised/shortened/reconsidered version of some of the content from these notes on the topic, which I posted on LessWrong and the EA forum -- though not on my website or substack -- last fall.

This might sound annoying. Don’t we already know what the alignment problem is? But I actually think we often don’t, really. And also, that some hazy conceptions of it bring a lot of baggage – baggage related, for example, to the idea that that “aligned” superintelligences need to be trustworthy even granted effectively arbitrary amounts of power (and/or, arbitrary opportunities to recursively self-improve).

Here I’m using the term “safety” in a distinctive and restricted way. I.e., I’m specifically talking about safety from loss of control scenarios, rather than any other forms (e.g., safety from misuse, safety from motivational problems that don’t involve misaligned power-seeking, etc). It’s possible that “control” would be a better term here (h/t Iason Gabriel for this suggestion), though that term comes with its own implications, too (for example, some people — influenced e.g. by Redwood Research’s “control” agenda — think of “control” specifically as referring to: making sure that an AI doesn’t have the option of causing something catastrophic, whereas safety in my sense can emerge from an AI’s options and motivations in combination).

Here “elicitation” means: the sort of task performance you get if an agent is trying its hardest to do the task in the desired way.

Note, here, that the role of the AI’s motivations is left open in this definition of “solving the problem.” It’s the safe elicitation of the capabilities that counts. This feature of my definition deviates from some standard usage – but that’s on purpose. More below.

It’s not always clear what counts as “one” AI vs. many – i.e., are different copies of GPT-6 “different AIs,” or the same? Generally, though, the main thing that matters for questions about coordination is (a) how easy is it for these AIs to coordinate, and (b) are they pursuing roughly similar terminal goals by default.

I emphasize this because sometimes people take comfort in ideas like “there will be a balance of power amongst the different AI systems” and “it will be too hard for these AIs to coordinate.” Even if true (is it?), this isn’t enough. It’s a bit like how: no single human or human group rules the world. And no single human group coordinated to take over. But humans became the dominant species on the planet regardless. Loss of control to rogue AI systems can be like that, but much faster.

Or to put my preference in another way: relative to “AI takeover,” I like the way “loss of control” puts the focus on the humans being disempowered, rather than on some particular set of AI systems imagined to have grabbed the reins. Indeed, no one in particular needs to have “the reins” – civilization can be as messy and uncoordinated as ever. But humans can be out, big-time, regardless.

Here’s one recent depiction that I appreciated, though of course we can poke at the details.

Where “voluntary,” here, includes “not manipulated or coerced.”

Law-abiding AI citizens would be one example here.

I first saw this spectrum articulated in some work by Ben Chang.

You might ask: don’t we already have superintelligence? For example: aren’t corporations and countries superintelligent agents of a kind? Well … kinda. Corporations and countries are better than individual humans at many tasks, yes. But not all. Yudkowsky, here, gives a nice example: if in 2000 (pre AlphaGo) you tried to get Microsoft, or Brazil, to play Go against Lee Sedol, it probably wouldn’t do a ton better than its best player. And in general, relative to individual humans, corporations/countries can be slower, less coordinated, etc.

Regardless, though: I’m defining Benefits specifically relative to the benefits of superintelligent AI. And superintelligent AIs would have a number of distinctive properties relative to both groups of humans and individual humans. For example: they do serial processing much faster than a human brain; they could be copied very cheaply; etc.

I’ll explain more about exactly how I define agents like this in my next essay, but roughly: agents who make and execute coherent plans, at least partly in pursuit of fairly long-term, consequentialist objectives, on the basis of sophisticated models of the world.

I’m doing this because they inherit human motivations and cognitive patterns by default, and thus are similar to humans with respect to many alignment-relevant issues. That said: the standards of “trust” we apply to a human would also change as their capabilities increase.

And obviously, they could raise ethical/political issues of their own, and create distinctive risks as well.

For example, if the main bottleneck to curing cancer is the serial time necessary to perform real-world experiments, it may be that the difference in how fast slightly-better-than-human-level AIs and superintelligences could cure cancer isn’t actually all that large. (Though: maybe. Or perhaps: the superintelligences would find much better ways to make use of limited data, speed up the process, etc.). The dynamic here might be similar to why it’s sometimes fine to use a smaller/weaker AI model for a given task. Thanks to Ryan Greenblatt for discussion here.

And obviously, even granted that you aren’t getting access to the main benefits of superintelligent AI agents, there’s a further important differences between e.g. getting none of those benefits, and getting some.

Obviously, I don’t mean: victory on all dimensions relevant to AI, the future, etc, going well. Victories on the alignment problem, in my sense, can still be bad overall. But they’re the key goal-states for the purposes of this series.

Solving the problem implies victory, in my sense (I’ll treat safe elicitation as a form of “access”). But avoiding and handling the problem are compatible with both victory and costly non-failure.

Though I think they sometimes also just mean: an approach at least scales past human-level-ish AIs to at least-minimally superintelligent AIs.

As I noted above, there’s a case to be made that we shouldn’t even try to think ahead to the challenges of superintelligence at all, and should instead focus on less powerful AIs – but I’m less sure about this.

Where, to be clear, “help” means “they’re probably doing effectively all the work.”

For this reason, I do in fact discuss the competitiveness of various alignment techniques in the series – though it’s not a major focus. And note that there’s an important difference between what we might call “development competitiveness” and “deployment competitiveness” – i.e., how large the alignment tax is for creating a safe AI, and how large the alignment tax is for using the safe AI. Large alignment taxes of the latter kind can quickly compromise the Benefits condition as I understand it (e.g., if safety requires a 1000x slow-down at inference time, that’s a very serious cost).

Though: not to actors that are aiming, purely, to build systems that are as powerful as possible, with no regard to whether those systems are aligned to any particular values. That said, note that if those systems then care about the alignment of the next generation, then they may be more cautious. Indeed, creating and preserving-across-generations extreme amounts of incaution/indifference with respect to the alignment of some next generation of AI systems may, itself, be a difficult alignment challenge, since it may be that only a fairly specific set of motivational systems don’t care about the alignment of the next generation.

Thanks to Buck Shlegeris for discussion of this possibility.

See e.g. the discussion of “the trouble with penalty terms” here. Basically, the idea is that the AI will find a way to satisfy the technical definition of these constraints, but that the constraints won’t be specified well-enough.

The general story here is that there is a convergent instrumental incentive towards both survival and “goal-content integrity” – i.e., it will generally promote an agent’s goals for future versions of itself to exist, and to share its current goals.

Valueless, that is, from according to our own values-on-reflection.

And in fairness, proponents of this story generally don’t advocate that we should aim, initially, for complete alignment. Rather, they think we should focus, first, on some more modest standard – i.e., “corrigibility,” “task-directed AI,” etc.

In particular: it seems to imply that any optimization that isn’t driven by the exact values of your current time-slice self points at doom.

Albeit, one that can function partly via controlling their options in addition to their motivations.

What is goodness? Well, we don’t know exactly. I don’t think we need to. And the term might not pick out the same thing for everyone. When I imagine what I want here in the nearer term, though, I imagine a civilization that is wise, awake, and with some core of joy, beauty, and love burning at its center. I imagine the horrors of our world ended. And I imagine a very large variety of stakeholders being happy with the situation.

And AIs aren’t just tools in this respect – they can be, in a richer sense, participants, citizens, and perhaps, ultimately, successors (though: figuring out the right way to incorporate AI systems as non-tools, if we should, is one of the challenges we need to grapple with; and I expect good futures to leave room for flourishing humans regardless). Nor, necessarily, does incorporating AI into good processes, in this way, require pointing optimization power directly at good stuff (i.e., optimizing for wisdom, consciousness, joy, etc). The alignment discourse often assumes that to get good stuff, you have to “optimize” for it directly. But I don’t think we should assume this.

Such that e.g. even if they could explain the situation to us fully, we’d make a “worse” decision, by our own lights, than they would.

For example: domains where we intrinsically value agency/understanding.

See e.g. Kulveit et al (2025) for some discussion of some ongoing potential problems.

Nor as “optimizing directly for your true utility function.”

Though sometimes, some background sense of needing to solve all other existential risks, at least, sneaks in.

I.e., its optimizing the future unboundedly on your behalf would lead to a good future from your perspective.

And to seek perpetually-stable “security” against losses of control brings its own risks. Indeed, I expect that one of the “transition benefits” of superintelligence will be greater clarity about what sorts of control we should or should not be seeking, and about how much the “good processes” at work in our civilization are driven by “control” vs. something else. More on some of the possible failure modes here.

And as I’ll discuss in a later essay, I think that giving AIs various types of power can also be useful, from a prudential perspective, in shifting their incentives away from “going rogue.” See also this paper for some discussion.

And/or: according to the “true” morality, if there is one.

It’s good to have a paper like this that fully explicates what is meant when we say a word that the industry has nearly obliterated with overuse. Well done. Are there any current alignment projects incorporating RL or other AI tech into their approaches that you’re excited about? I feel like humans vibing their way to value sets for safety and control may be a more short-lived solution than we thought a year ago.