(Podcast version here, or search "Joe Carlsmith Audio" on your podcast app.)

"What was it then? What did it mean? Could things thrust their hands up and grip one? Could the blade cut; the fist grasp?"

1. Introduction

Ethical philosophy often tries to systematize. That is, it seeks general principles that will explain, unify, and revise our more particular intuitions. And sometimes, this can lead to strange and uncomfortable places.

So why do it? If you believe in an objective ethical truth, you might talk about getting closer to that truth. But suppose that you don’t. Suppose you think that you’re “free to do whatever you want.” In that case, if “systematizing” starts getting tough and uncomfortable, why not just … stop? After all, you can always just do whatever’s most intuitive or common-sensical in a given case – and often, this is the choice the “ethics game” was trying so hard to validate, anyway. So why play?

I think it’s a reasonable question. And I’ve found it showing up in my life in various ways. So I wrote a set of two essays explaining part of my current take.1 This is the first essay. Here I describe the question in more detail, give some examples of where it shows up, and describe my dissatisfaction with two places anti-realists often look for answers, namely:

some sort of brute preference for your values/policy having various structural properties (consistency, coherence, etc), and

avoiding money-pumps (i.e., sequences of actions that take you back to where you started, but with less money)

In the second essay, I try to give a more positive account.

Thanks to Ketan Ramakrishnan, Katja Grace, Nick Beckstead, and Jacob Trefethen for discussion.

2. The problem

There’s some sort of project that ethical philosophy represents. What is it?

2.1 Map-making with no territory

According to normative realists, it’s “figuring out the normative truth.” That is: there is an objective, normative reality “out there,” and we are as scientists, inquiring about its nature.

Many normative anti-realists often adopt this posture as well. They want to talk, too, about the normative truth, and to rely on norms and assumptions familiar from the context of inquiry. But it’s a lot less clear what’s going on when they do.

Perhaps, for example, they claim: “the normative truth this inquiry seeks is constituted by the very endpoint of this inquiry – e.g., reflective equilibrium, what I would think on reflection, or some such.”2 But what sort of inquiry is that? Not, one suspects, the normal kind. It sounds too … unconstrained. As though the inquiry could veer in any old direction (“maximize bricks!”), and thereby (assuming it persists in its course) make that direction the right one. In the absence of a territory – if the true map is just: whatever map we would draw, after spending ages thinking about what map to draw – why are we acting like ethics is a normal form of map-making? Why are we pretending to be scientists investigating a realm that doesn’t exist?

2.2 Why curve-fit?

My own best guess is that ethics – including the ethics that normative realists are doing, despite their self-conception – is best understood in a more active posture: namely, as an especially general form of deciding what to do. That is: there isn’t the one thing, figuring out what you should do, and then that other separate thing, deciding what to do.3 Rather, ethical thought is essentially practical. It’s the part of cognition that issues in action, rather than the part that “maps” a “territory.”4

But on this anti-realist conception of ethics, it can become unclear why the specific sort of thinking ethicists tend to engage in is worth doing. Here I’m thinking, in particular, about the way in which ethics typically involves some sort of back-and-forth between particular intuitions about what to do in specific cases, and more general principles that explain and revise those intuitions. That is, roughly, ethics typically implies some effort to systematize our pattern of response to the world; to notice the contradictions, tensions, and coherence-failures that arise when we do; and to revise our policies accordingly, into a more harmonious unity.

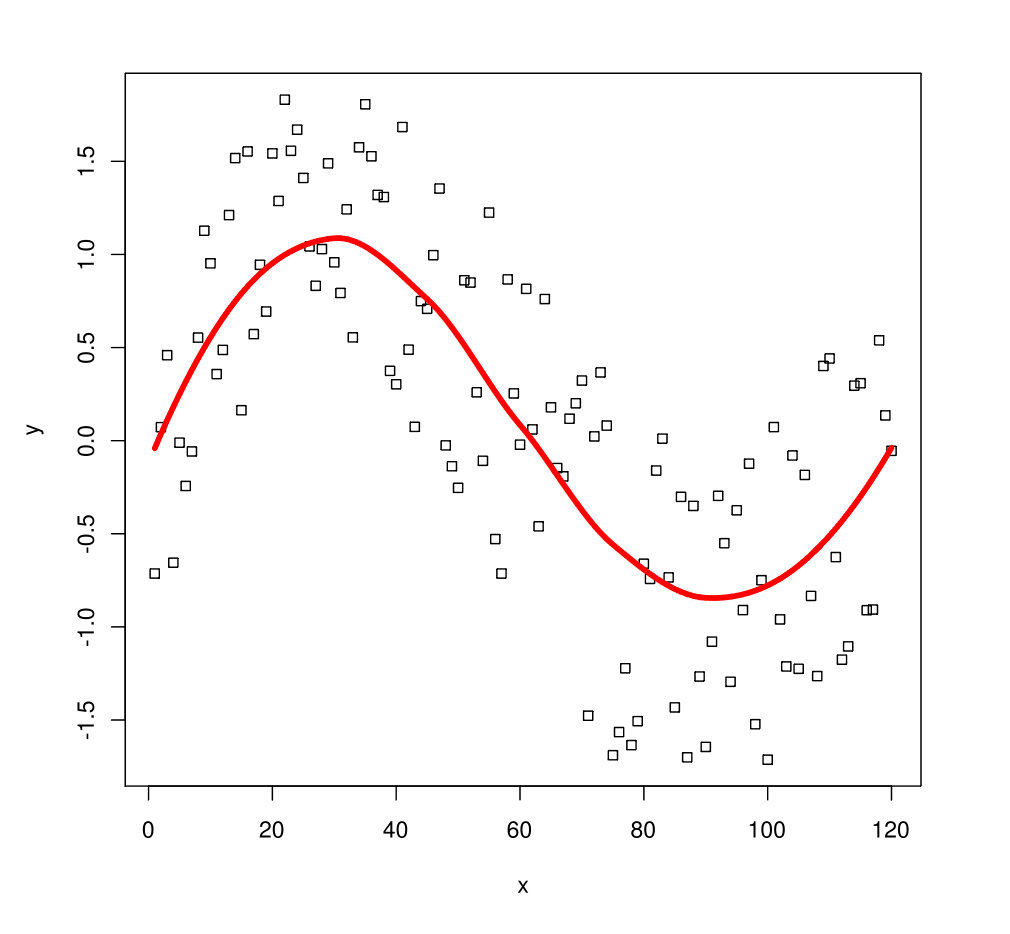

But why do this? The standard practice – both amongst realists and anti-realists — often works within an implicitly realist frame, on which one’s intuitions are (imperfect) evidence about the true underlying principles (why would you think that?), which are typically assumed to have properties are like consistency, coherence, and so on. To find these principles, one attempts to “curve fit” one’s intuitions – and different ethicists make different trade-offs between e.g. the simplicity and elegance of the principles themselves, vs. the accuracy with which they predict the supposed “data.”5 But if this practice isn’t helping us towards the objective normative truth, why would we go in for it?

Why do this to yourself? (Image source here.)

Consider, for example, the following policy: “whatever, I’m just going to do whatever I want, or whatever seems intuitively reasonable, in each particular case.” Boom: done. And with such amazing fidelity to our intuitions in each case! The curve is just: whatever the curve god-damn needs to be, thank you. Or if that doesn’t work: screw the curve. I’m a no-curve dude. Going with my gut; with common-sense; with “what my body wants”; with that special, rich, heuristic wisdom I assume I bring to each decision. Metis, you know? Coup d’oeil. Wasn’t that what the curve fitting was trying so hard to validate, anyway? Now can I get back to what I was doing?

Of course, one objection to this is just: it looks like the type of thing slaveholders could have said. That is, to the extent your default policy/intuitions are wrong, this approach won’t set them right. But the anti-realists have not yet made good on the notion of a policy being “wrong,” or on a story about why systematizing would notice and correct this wrongness.6 Isn’t it all, just, what you decide to do? So if you in fact decide to do blah, or want to do blah, why not just the draw the curve in a way that validates that decision? Indeed, why draw curves at all?

A second objection is: this approach doesn’t allow for a very simple or compact description of your policy, or your “true values,” or whatever. The curve, if you draw it, seems over-fit; it’s not the sort of line we’d want to draw in stats class. And indeed: yes. But, um… who cares? Yes, in empirical contexts, we typically think simpler models will be a better guide to the truth.7 But we already said that there was no truth to be a guide to, here. Why would we import map-making norms into a domain with no territory?

Is the worry that you won’t be able to predict, using some explicit model of your values, what your intuition/choice will be in a given case? Maybe there’s something important here (more in the next essay).8 But naively: ethics is not about self-prediction (and people, including yourself, can presumably make predictable ethical errors); and you can always ask yourself, directly, what your intuition in the relevant cases would be.

A third objection is: this sort of policy won’t be very helpful in guiding action. That is, if you encounter a new sort of situation, where your intuition does not immediately yield a verdict about what to do, you are left bereft of general principles to fall back on. I think this is getting at something important, but on its own, it doesn’t feel fully satisfying. In particular: often our intuition does provide some sort of guidance about a given case, and the pressing question is whether our intuition is correct. And to the extent our intuition falls silent in some cases, what’s wrong with “crossing that bridge when we come to it?” – which for many of the hard and artificial cases philosophers focus on, we generally won’t (a fact that non-philosophers are often quite impressed with). Perhaps, indeed, I don’t have an explicit method of making all my decisions ahead of time. But who said I needed one?

2.3 Who needs ethics if you’re free?

I think these are good questions. And I find that they come up a lot.

For example: my realist friends often say that if they became anti-realists, their approach to ethics would totally change. In particular, their commitment to structural things like “consistency,” “coherence,” and “transitivity” would go out the window; and their interest in more substantive stuff – like helping others, scope-sensitivity, etc – would diminish strongly as well.

Also, they’d be way less willing to bite the sorts of bullets they’ve managed to force themselves to bite – bullets like the repugnant conclusion (my realist friends tend to be total utilitarians, modulo moral uncertainty). That is, if they were free — if they could just do what they want to – then obviously they wouldn’t go for a zillion slightly-happy lizards (plus arbitrary hells?) over Utopia: are you kidding me? Lol. Those lizards are a nightmare. Oh yes, it’s a nightmare they’re devoting their lives to.9 But that’s because apparently it’s the true morality. Yes, it’s a bit rough. They admit the true morality could’ve been way better. They walked out of Plato’s cave and they were like: yikes. If they had their way, they’d go for Utopia, trust them. It’s just that duty (optimality, beneficence) calls.

But I see a similar impulse amongst anti-realists as well. For example: there is a live debate, amongst my friends, about what to do when systematic reasoning starts to lead to new and uncomfortable places, and one candidate response is just “idk, just stop doing systematic reasoning, whatever.” This debate isn’t limited to ethics in particular (rather, it’s tied in with broader debates about inside views, epistemic learned helplessness, cluster thinking, and so on); but a “whatever” answer to an otherwise forceful ethical argument can easily seem a more live option if ethics is a domain where ultimately, you can just “do whatever you want.” I.e., “whatever” amounts to something like “draw the curve however I need to in order to keep doing what I want to do anyway; or don’t draw it at all, I don’t care.”

3. Some examples where this stuff comes up

In considering these reactions, I think it’ll help to have a few concrete examples of “ethics” on the table. Here are two.

3.1 Drowning children stuff

Consider the following three (perhaps familiar) claims.

It’s impermissible to let a nearby child drown in order to not ruin an expensive suit.

It’s permissible to buy a suit instead of donating the money to save a distant child.

There is no morally significant difference between these cases.

(1)-(3) all seem initially intuitive. But they’re also inconsistent.10 So the realist says: “one of them must be false.” One assumes that a real domain can’t be inconsistent, after all.

But for the anti-realist, it’s less clear how to relate to this inconsistency. After all, we’re not trying to draw a map of some external domain. So does the anti-realist really need to give one of these up? Could we, maybe, give up on philosophy instead? Is there a “whatever” option?

I remember talking with a realist friend about this sort of case. He takes it very seriously. But he said that if he was an anti-realist, he wouldn’t. Rather, he would just … something. I assume: buy the suit. But not in a “I hereby reject 3, and posit a morally significant difference between the cases” way. Rather, in some other way – some way less interested in the “whole game.”11

3.2 Lizard stuff

Or consider the following argument for the Repugnant Conclusion:12

Benign Addition: If world x would be the result of improving the lives of everyone in world y, plus adding some new people with worthwhile lives, then x is better than y. (Less formally: helping everyone who exists, plus adding some net-positive lives on the side, is good.)

Non-anti-egalitarianism: If world x and world y have the same population, but x has a higher average utility, a higher total utility, and a more equal distribution of utility than y, then x is better than y.13

Transitivity: If x is better than y and y is better than z, then x is better than z.

These principles all look pretty solid. Benign Addition is basically a Pareto-principle (i.e., a “better for some, at least as good for everyone” thing), combined with the absence of active opposition to new happy lives. Non-anti-egalitarianism seems strong by totalist AND averagist AND egalitarian lights (and because it assumes a constant population, it will fall out of Harsanyi-ish utilitarian arguments as well). And Transitivity seems super structural and obvious (see also here for more substantive arguments in its favor; plus a bit more below).14

Yet in combination, these principles imply (at least in conjunction with some assumptions about lizard welfare, and welfare comparisons more broadly) that for any finite Utopia, there’s a better world consisting entirely of barely-happy lizards. (See footnote if you’re unfamiliar with this reasoning.15)

Which is your favorite?

Also: note that if you’re getting tripped on something about creating new people, we can run a version of this argument that just appeals to extending your own life, lizard-style.16 That is: just re-interpret the diagrams above as graphing the quality of your possible lives over time (see footnote for more detailed reasoning).17 Thus, faced with the option of a wonderful human life, you transform yourself, instead, into a (very long-lived) lizard.

Your next zillion years. (Photo source here)

3.3 Scott Alexander on rejecting the “philosophy game”

People say philosophy doesn’t make progress. But I think it makes lots of progress.18 The progress isn’t necessarily of the form: “you must become lizard.” Rather, it’s often of the form: you can’t have all of x, y, and z.19 Drowning children and repugnant conclusions are both great examples.

Still, progress of this kind is often painful. Sometimes, we wanted x, y, and z. We wanted it all. Must the dream die?

Indeed, some anti-realists confront this sort of pain and go: “I’m out.” This, for example, is a tempting reading of Scott Alexander’s response to the repugnant conclusion thing above, in his review of What We Owe the Future.20 Let’s look briefly at that review.

Part of Alexander’s response is a gesture at a way of rejecting Benign Addition (“If I had to play the philosophy game, I would assert that it’s always bad to create new people whose lives are below zero, and neutral to slightly bad to create new people whose lives are positive but below average”), but I don’t want to focus on that here: Alexander anticipates that his object-level proposal might imply further serious problems, and I think he is very right (see footnote for a few examples).21

Rather, the heart of Alexander’s response, at least in the initial review, seems to be some more wholesale rejection of philosophy itself – or at least, what he imagines philosophy to be:

You’re walking along, minding your own business, when the philosopher jumps out from the bushes. “Give me your wallet!” You notice he doesn’t have a gun, so you refuse. “Do you think drowning kittens is worse than petting them?” the philosopher asks. You guardedly agree this is true. “I can prove that if you accept the two premises that you shouldn’t give me your wallet right now and that drowning kittens is worse than petting them, then you are morally obligated to allocate all value in the world to geese.” The philosopher walks you through the proof. It seems solid. You can either give the philosopher your wallet, drown kittens, allocate all value in the world to geese, or admit that logic is fake and Bertrand Russell was a witch…

But I’m not sure I want to play the philosophy game. Maybe MacAskill can come up with some clever proof that the commitments I list above imply I have to have my eyes pecked out by angry seagulls or something. If that’s true, I will just not do that, and switch to some other set of axioms. If I can’t find any system of axioms that doesn’t do something terrible when extended to infinity, I will just refuse to extend things to infinity. I can always just keep World A with its 5 billion extremely happy people! I like that one! …

I realize this is “anti-intellectual” and “defeating the entire point of philosophy”. If you want to complain, you can find me in World A, along with my 4,999,999,999 blissfully happy friends.

(Alexander also includes a meme saying “just walk out; you can leave!” and “if it sucks, hit da bricks! Real winners quit” regarding “thought experiments that demonstrate that you have intransitive preferences.”)

What’s going on here? What does it mean to “not play the philosophy game”? What is this “quitting” that “real winners” do?

Alexander seems intent on avoiding something. For example, he wants to avoid starting down paths that seem nice but go somewhere horrible. And my sense is that more generally, he wants to avoid the sort of thing epistemic learned helplessness is supposed to protect against: namely, being tricked into stupid conclusions by listening to arguments.

But where does he hope to end up instead? Well, he says something about this. We know he’s pro-Utopia. He’s anti-repugnance. And damnit, he’s going to draw whatever curves he needs to in order to stay that way. Of course, he doesn’t know what those curves are. It’s not clear he wants to. Probably, they imply some horrible thing. But it’s OK, he will just not take them there; he will just not do that horrible thing. See? Easy. Do philosophy until, fuck it, you stop.

Or at least, that’s the vibe I get from Alexander’s original review. In a follow-up piece, his tone seems a bit different. In particular: he acknowledges that “realistically I was doing philosophy just like everyone else.” And his main position seems to be that he is entitled, as an anti-realist, to build his ethics around avoiding the repugnant conclusion if he wants to;22 that “I prefer to leave this part of population ethics vague until someone can find rules that don’t violate my intuitions so blatantly” and that “I know that it’s not impossible to come up with something that satisfies my intuitions, because ‘just stay at World A’ (the 5 billion very happy people) satisfies them just fine.” I still think Alexander isn’t grappling with the full force of the bind he’s in, here (see footnote for more),23 but I don’t want to focus too much on his view in particular.

Rather, I’m more interested in the broader vibe that his initial review conjured, at least for me – one that I don’t think Alexander would actually endorse (at least not in the tone I’m offering it), but which I wonder if others might take away from his comments. It’s a vibe like: maybe ethics is hard for the realists. Maybe they should be scared of that old word, “implication.” For them, perhaps, such a word has heft and force. It might tell you something new about factory farms, or slavery.24 Something that somehow, you weren’t seeing before (what is this not-seeing?). It might change your life.

But for anti-realists, on this vibe, “implication” goes limp and wispy. It’s just curve-stuff, and you are not bound by curve-stuff. Not once you have learned words like “whatever.” If some curve says “do blah,” but you don’t want to, you can just say “nah.” Thus, you are safe. Right?

4. I’m not trying to turn you into a lizard

I’m going to be defending “the philosophy game” a bit in what follows, so I want to be clear about something up front: I’m not trying to turn you into a lizard, or to take away your suits.25 On anti-realism, if you don’t actually want to become a lizard, or to pave the world with lizard farms, or to donate all your money to blah, or whatever – then you never have to. That’s the whole “freedom” thing. It’s the truth in “whatever.” It’s also a key part of what Alexander, as I read him, is trying to hold on to – he can, indeed, just keep World A, if he wants – and I think he’s right to try to hold on to this.

Indeed, I think that often, what people are groping for, when they talk about stuff like “not playing the philosophy game,” is something about not being coerced by philosophy – and especially not philosophy they don’t really believe in, but have some sense that they “should.” Note, for example, the way that Alexander, in the original review, is experiencing philosophy as coming from the outside and “mugging him.” Philosophy is an adversary.26 It might seem innocent and truth-seeking. But it’s trying to pull some clever trick to get him to give up something he loves; to cut him, with some cold and apparently-rigorous violence, into something less than himself. It’s re-assuring him that “no, really, I know it hurts, but it’s all a matter of logic, there’s no other way, you saw the proof.” But some part of him doesn’t buy it. Some part of him moves to protect itself. And I do actually think that stuff about epistemic learned helplessness is relevant here; and also, stuff about bucket errors.

Indeed, this sort of frame can make sense of some of the realist reactions above, too. “If I wasn’t being coerced by the normative truth, then why would I be doing any of this stuff?” (Though note that not all authority is coercion – especially conditional on realism.)

But I think there’s a way of doing philosophy that isn’t like this. A sort of philosophy that is more fully “on your side.” That’s the sort I want to defend.

Most of my defense, though, will be in my next essay. Here, I want to talk about two defenses that don’t seem to me fully adequate, namely:

Appeals to some kind of brute preference that your policy have various structural properties

Appeals to money-pumps and “not shooting yourself as in the foot” as an argument for “coherence”

5. Some kind of brute preference for consistency and systematization?

Anti-realism, famously, treats something like brute desire/preference as the animating engine of normative life. So to the extent anti-realists think they have some kind of reason to engage in the “systematizing” type of ethics at stake here, it’s natural to wonder whether this reason will stem from some kind of brute preference/desire that one’s values have various structural properties: things like consistency, coherence, simplicity, systematic-ness, and so on.

That is, on this story, trying to resolve the tensions implied by drowning children/repugnant conclusions/whatever is, sure, one thing you can be into. Apparently, you’re a “systematizer.” And that’s fine! It’s really fine. Personally, though, I collect stamps.

My sense is that this is what realists often think is going on with anti-realists who still care about ethics for some reason, despite its conspicuous absence of subject-matter. (Well: that, and not having really shaken their implicit allegiance to realism.) And some anti-realists seem to think this way, too. Thus, for example, I get vibes in this vicinity from the following comments from Nate Soares:

So I look upon myself, and I see that I am constructed to both (a) care more about the people close to me, that I have deeper feelings for, and (b) care about fairness, impartiality, and aesthetics. I look upon myself and I see that I both care more about close friends, and disapprove of any state of affairs in which I care more for some people due to a trivial coincidence of time and space.

And I am constructed such that when I look upon myself and find inconsistencies, I care about resolving them.

One problem with this sort of story is that it struggles to justify ethics as it’s actually practiced (including by anti-realists), especially with respect to stuff like consistency. In particular: it treats stuff like “avoiding inconsistency” as one-value-among-many, which naturally suggests that it would be “weighed in the mix.” In practice, though, ethicists treat consistency as a hard constraint (note that this is different from saying that different values can’t pull in different directions). And they’re right to do so, even conditional on anti-realism.

Thus, for example, suppose you have decided to buy the suit. But you’ve also decided not to buy the suit. Ethics doesn’t say: “ah, OK, well one other thing to factor in here is that you value being consistent – just want to throw that in as an additional consideration.” Indeed, on its own, it’s not clear why this would be enough to prompt a resolution to the conflict. But ethics goes a different route. It says: “Sorry, this policy you’re trying to have, here, just isn’t a thing. Either you’re going to buy the suit, or you’re not, but you’re not going to do both.”

And the same goes for inconsistencies at a more abstract level. Consider: “I will always give everyone equal consideration,” and “I will be especially helpful to my friends.” Oops: not a thing.27 Same for: “I will blame people who don’t save nearby drowning children” and “I won’t blame people who buy suits” and “I will either blame both suit-buyers and nearby-children-let-drowners, or I won’t blame either of them.”28 Just: not a way-you-can-be. And that’s just true in the standard sense. Your idiosyncratic, quasi-aesthetic, “systematizing” preferences don’t come into it.

I care about this example because sometimes, in a conversation in which some ethical inconsistency gets pointed out, people will act as though “eh, I don’t care that much about being ethically consistent” is some sort of viable path forward – and indeed, perhaps, a tempting freedom. After all: if you’re up for inconsistency, you can have it all, right? No. The whole thing about consistency is that it tells you what you can have. This is as true in ethics as elsewhere, even on anti-realism — and true regardless of your preferences, or your attitudes towards the “philosophy game.”

Of course: often, in such contexts, people aren’t actually talking about literal consistency. Rather, they mean something more like: treating apparently-similar cases alike; or: applying apparently-compelling principles without exceptions; or maybe they’re not distinguishing, cleanly, between intransitivities (A ≻B ≻C ≻A) and direct inconsistencies (A ≻B and not(A ≻B)).29 And in those cases (depending on how we set them up), we can’t always appeal to stuff like “your proposed policy is just not a thing.” For example, there is indeed a policy that takes world A+ over world A (it likes Benign Addition), world Z over world A+ (it likes Non-Anti-Egalitarianism), and world A over world Z (it hates the Repugnant Conclusion) – and which does, idk, something when faced with all three.

Still, the same broad sort of worry will apply: namely, that to the extent ethics wants to treat blah-structural-property as a hard constraint, saying “I happen to care, intrinsically, about my policy having blah-structural-property” looks poorly positioned to justify allowing this particular preference such over-riding power – assuming, that is, that you care about other stuff as well. For example, faced with the intransitive policy above, if you throw in “also, I happen to care about satisfying Transitivity,” then fine, cool, that’s another thing to consider. But: how much do you care about that? Enough to ride the train to lizard land? Enough to give up on “helping everyone + doing something neutral/good is good”? There are other cares in the mix here, too, you know…

That said, one response to this is just: fine, maybe stuff like transitivity shouldn’t be a hard constraint. Maybe it should be just one-value-among-others.

Even if we go that route, though, I feel some deeper objection to “I do ethics, as an anti-realist, because I have a brute, personal preference that my values/policy have blah-structural-properties.” In particular: at least absent some more resonant characterization (more in my next post), it just doesn’t seem compelling to me – especially not next to more object-level, hot-blooded ethical stuff: next to suffering, death, joy, oppression; donating all your money to charity; joining the communist party; destroying Utopia to build a lizard farm; and so on. If some dilemma pits real, object-level stakes, on the one hand, against my degree of brute preference to satisfy some abstract structural constraint, on the other, why expect the latter to carry the day? And if ethics, for anti-realists, gets its oomph solely from the latter, I worry that it’s calling on something too dry and thin.

6. Money-pumps

Let’s turn to a different sort of justification for caring about systematic ethics, even as an anti-realist: namely, the idea that if your values don’t have various structural properties that ethicists are sometimes interested in, then you’re vulnerable to “money-pumps” – i.e., paying money to go in a circle.30

Thus, for example, the intransitive policy above looks like it would pay money to switch from A to A+ to Z and then back to A. And no matter your meta-ethics, or your attitudes towards marginal lizards, this seems pretty dumb. In particular: it seems like burning money for no reason (was there a reason, though?). And also, the fix seems cheap: instead of doing it, don’t. So cheap! Indeed: free. Indeed: profitable. Transitivity, apparently, is free money. And we can construct similar arguments for the other axioms of von Neumann Morgenstern (vNM) rationality (see here for discussion of such arguments) – axioms that together imply that your values need to be representable as a consistent utility function, which sounds pretty “systematizer”-ish.

Is “don’t burn money for no reason” enough of an impetus for doing systematic ethics, even as an anti-realist? Is the main objection to a policy of “whatever, draw the curves in whatever way, I’m just going to do whatever I want” something like: “OK, but I can see parts of your policy that could, in combination, end up burning money for no reason – don’t you at least want to eliminate that?” And if you try to do so, do you end up re-shaping yourself into an expected utility maximizer?

I used to like this argument a lot. Now I like it less.

6.1 Dialogue with an intransitive agent

I started to get suspicious of it after a number of conversations (partly with myself) in the following vein:31

Them: Jesus, this lizard stuff is horrible. I think I’m just going to accept that my preferences are intransitive. After all: fuck it, I’m an anti-realist.

Me: OK, but you’re going to get money-pumped.

Them: Um, will I? These cases don’t seem very real-world, anyway.

Me: I dunno, is it so easy to tell where these intransitivities show up? But also: in principle though.

Them: I think what I’ll do is like: if I see that I’m about to get money-pumped, I’ll just not. Like, if A ≻B ≻C ≻A, and I see that I’m going to have access to sets of options that allow me to get any of them, then I’ll just pick one (the same one I’d choose in a three-way choice), make a plan to get it, and stick with that plan.32

Me: I think there’s some supposed to be some sort of more sophisticated money-pump where that doesn’t work?

[Checks briefly in Gustafsson’s book on Money Pumps.]

Me: OK actually looks Gustafsson’s main objection amounts to something like “it’s irrational to keep your commitments if they run counter to your later-preferences,” which I don’t buy.33 I think the fancy cases were about “backward induction,” which is different. Still, though: what if you don’t know what options you’ll have in the future?

Them: Hmm, I think it’s fine to trade in a circle, if you get new information along the way? Like, suppose I have a ticket to the circus, but then I pay to trade it for an opera ticket, but then I learn that my favorite opera star is out sick, so I pay to trade back.

Me: This seems different somehow? Like, all you’re getting is new information about what options you’ll have in the future, not about how good they are. And I think you’ll end up with vibes like “if my choices are chocolate and vanilla, I’ll take chocolate; but if I then learn that strawberry is on the menu as well, I’ll pay to switch to vanilla.” This seems worse than the opera thing.

Them: [Does some hazy calculation of the expected amount of money/resources/value lost to this sort of unforeseen money-pumping.] Eh, whatever, doesn’t seem like a super big cost relative to that lizard stuff.

Me: Hmm…

Them: Also, is that sort of thing always bad? Suppose I prefer having a moderately happy child to having no child; I prefer having no child to having a very happy child and paying for a very expensive operation; but if I have a moderately happy child, and an operation is available to make them very happy, I will be obligated to pay for it (so I prefer to do so). Now suppose that at T1, I believe that no operation is available, so I pay to become pregnant with a child who will be moderately happy. Then, at T2, I learn that the operation is in fact available, and I believe that it is too late to call off the pregnancy, so I pay to sign up for the operation. Finally, at T3, I learn that in fact, the pregnancy hasn’t yet occurred, so I pay to avoid becoming pregnant at all.34 Here, I have paid to trade in a circle. But not clear I was irrational in doing so?

Me: OK but we can re-interpret that case in terms of the worlds at stake having different properties: e.g., your having violated an obligation vs. not.35

Them: I dunno, seems like the sort of thing you were supposed to be against. And I worry we’re going to “re-interpret” things until your position doesn’t have any content except when you want it to.

Me: … but, like, intransitive preferences… like, what are you even doing with your life, yano?

Them: What? I thought this was supposed to be about not burning money.

To be clear: I don’t think I am here representing all there is to be said in this sort of dialectic. And I think there are strong arguments for transitivity that don’t proceed via literal money-pumps.

Thus, for example, intransitivity requires giving up on an especially plausible Stochastic Dominance principle, namely: if, for every outcome o and probability of that outcome p in Lottery A, Lottery B gives a better outcome with at least p probability, then Lottery B is better (this is very similar to “If Lottery B is better than Lottery A no matter what happens, choose Lottery B” – except it doesn’t care about what outcomes get paired with heads, and which with tails).36 [EDIT 2/17: Oops: actually, this isn't the right way to formulate the principle I have in mind. But hopefully the example can give a flavor for what I’m going for.] To see this, suppose that Apples ≻ Oranges ≻ Pears ≻ Grapes ≻ Apples. And now consider the lotteries:

50% Apples, 50% Pears

50% Oranges, 50% Grapes

Apples are better than Oranges, and Pears are better than Grapes (and the probabilities are all equal). So by Stochastic Dominance, I is better than II. But also: Grapes are better than Apples, and Oranges are better than Pears. So by Stochastic Dominance, II is better than I. Thus, faced with a choice between I and II, you decide to choose I, and you decide to choose II. Oops, though: that’s one of those “not a thing” situations.

I expect tons of this sort of thing if you actually go in for Intransitivity, and try to propagate it through your decision-making as a whole, rather than just patching specific problem cases when people force them to your attention. Indeed, I expect lots of stuff to just stop making sense (though: whether it will make less sense than intransitivity itself is a different question).

But money-pump arguments aren’t supposed to be about what “makes sense.” What is “making sense” to a free-thinking anti-realist? Sounds like curve-stuff to me. Stochastic Dominance, for example, sounds like a curve, and that thing about I and II, like one of those “implication” things. Didn’t we get free from all that? Faced with a choice between I and II, maybe the anti-realist says: “idk man, whatever, pick whichever one you want.”37

No, money-pump arguments are supposed to punch at a more guttural level, to speak in a language that even a free-thinker will understand and take seriously: namely, your love of raw power (money). Or, like, your love of whatever it is you want to do with power, which I guess is like, Apples? Or wait, Grapes? Actually I don’t really know what you want to do with your money.38 But whatever it is, money-pump arguments assume, you like more money rather than less. “Coherence” (i.e., something like: being a VNM-rational agent) can get you more; ethics (on this story) is basically about re-shaping yourself into something more coherent; so ethics, apparently, pays out in free money. And isn’t that enough of an argument in its favor, even for anti-realists?

6.2 Coherence isn’t free

I think there’s something to this line of thought, but I’m skeptical that it can bear the weight some people I know want to put on it.

For one thing, the circumstances that money-pump arguments focus on – namely, ones in which you literally trade in a circle, or end up “strictly worse off” than you would’ve been otherwise – seem comparatively rare in real life (and this even setting aside the thing where you can interpret any sequence of trades as maximizing for some consistent utility function over entire-world-histories – more here). That is, strictly speaking, the money-pumper only gets to say “gotcha!” if you start with A, then end up back at A later, but with less money (plus something something, you didn’t learn new stuff in a way that makes this OK, or something). But in real life, it’s not clear to me how often this sort of strict “gotcha!” actually comes up, especially once we start bringing in various hacky strategies for avoiding it, like the “resolute choice” thing above. And for anything other than a strict “gotcha,” it’s not clear that it’s a gotcha at all, if you’ve started being sympathetic to intransitivity more generally.

What’s more, I think that various “whatever”-ish anti-realists, like the one in the dialogue above, sense this. That is, confronted by money-pump arguments, they do a quick forecast of how much money/power/fruit etc they can actually make by correcting some incoherence in themselves, notice that it doesn’t seem like a lot, and shrug it off. Maybe coherence is, like, a bit of extra power; but how much are we talking? Would it, maybe, be better, from a money/power/whatever perspective, to spend some time practicing public speaking? Or, to go on a jog? Is resolving this stuff about lizards really the best way to win friends and influence people?39

One possible response here is: “ah, but public speaking/jogging etc aren’t free power. But coherence is. Being coherent is just: not shooting yourself in the foot, not stepping on your own toes, not doing something strictly worse than some alternative. So it’s an especially clear-cut win.” But I think this sort of rhetoric mischaracterizes the sort of dilemma that incoherence creates (and not just because reading philosophy books takes time/energy/etc, just as anything does).

In particular: resolving incoherences in yourself isn’t always free. Often, to the contrary, it’s quite painful. Your initially intransitive preferences were, after all, your real preferences. They weren’t some silly “oopsie.” Some part of your heart and/or your mind had a stake in each of them. So any way of cutting the circle into a straight line involves cutting some part of your heart/mind off from something cared-for. Why are we acting like doing this is free? The fact that people are even thinking about rejecting transitivity, despite its apparent obviousness, is testament to its costs.

Suppose, for example, that A ≻ B ≻ C ≻ A, you start with A, and you end up paying a dollar to end up back at A. Money-pump-arguers often want to say that this is a “dominated strategy,” in a way that suggests that there’s some easy and obvious fix. But what should you have done differently? If you just stick with A, and refuse to trade for C, then you do violence to C ≻ A. If you trade to C, and stop, you do violence to B ≻ C. If you trade to B, and stop, there goes A ≻ B. Apparently, to avoid this money-pumping, some part of you needs to die, change, reform. But what if you care more about each of those parts than you do about an extra dollar?

Perhaps you say: “Ah, but if I pretend that each of those parts has their own little mini-utility function, or even some ‘more of X is always better’ thing, then I can prove that you’ll get pareto-improvements by making yourself coherent and picking some consistent way of trading those goals off of each other.”40 And I do think that there’s often something useful about this sort of frame. But note, in this particular case, that it’s imputing way more structure, to these parts, than the case has offered. My preference for A over B, here, isn’t saying “maximize A-ness!” Rather, it’s saying “given a choice between A and B, choose A.” That’s all. It’s not a full-fledged rational agent (and the whole question, here, is whether becoming such an agent is especially compelling, if you aren’t one already). It’s a preference about a specific choice situation. And it, or something like it, is going to get disappointed.

Really, there are lots of different coherent agents you could become, here. Yes, each of them wants extra money. But you’re not any of them, yet, and dangling a dollar as a prize doesn’t resolve the question of which one to become, if any, or render making the choice costless from your current perspective.

(Flip a coin? Less arbitrary, yes. But still not free – still a part of you dying in expectation. And anyway, is that the right way to approach questions about the repugnant conclusion? Flip a coin about whether to become a lizard?)

We see, here, the same sort of problem we ran into in the last section, when we tried to treat coherence in itself as some kind of brute terminal value. Here, we’re trying to treat coherence as an instrumental value instead. But even granted some sort of value of this kind, we still end up asking: OK, but how much is it worth? And this question becomes especially pressing if we’re trying to treat coherence as some kind of hard constraint on the type-of-agent-you-should-be, as many advocates of money-pump arguments seem to want to. If the instrumental value at stake were “free,” that might help to motivate grabbing such value as a hard constraint (or rather: a “why wouldn’t you”?). But it’s not.

6.3 Can we even think outside of a rational agent ontology?

But I think there’s also a deeper problem with this sort of money-pump argument: namely, that it’s trying to speak in the language of some sort of “incentive” to make yourself coherent, but its central understanding of “incentives” arises from within a certain sort of familiar, rational-agent ontology: i.e., one where different agents run around optimizing for their utility functions. And it’s precisely the question of whether to become such an agent that the “incentives” at stake are supposed to resolve.

That is: it feels like what the money-pump argument really wants to say is “you’ll get more utility if you become coherent.” But it keeps having to catch itself, and say something muddier (maybe: “whatever your utility function, you’ll get more utility” – but you don’t have such a function!), because you’re not an agent for whom “utility” is a thing (at least not in the standard way). So it doesn’t, actually, know how to talk to you. And if it did, it wouldn’t need to.

Or to put things another way: money-pump arguments try to shoe-horn “rationality mandates self-modifying to become an agent with a consistent utility function” into an implication of that more familiar slogan, “rationality is about winning.” But messing with your values (without the aim of maximizing for some other set of values) is actually very different from “winning.” Indeed, it’s relative to your values that “winning” gets defined. And here anti-realist rationality leaves the terrain it knows how to orient towards. Give anti-realist rationality a goal, and it will roar into life. Ask it what goals to pursue, and it gets confused. “Whatever goal would promote your goals to pursue?” No, no, that’s not it at all.

We see this same sort of tension, I think, in the appeal that many anti-realists want to make to your “values on reflection,” or your “coherent extrapolated volition,” or whatever. At bottom, the core role of such appeals often seems to me something like: “I know, I know, you don’t have a utility function. But: this makes me confused. So I’m going to say: yes you do. It’s just, um, hiding. Like the tree inside a seed. We just need to compute it. Great: now back to the rational-agent ontology.”

Oversimplifying: the problem is that anti-realist rationality (at least in its naïve form) can only think about three things. One thing is like: single agents, optimizing for a utility function. Another thing is: game theory, between different agents with utility functions (e.g., stuff about conflict, bargaining, negotiation, etc). A third thing is: brute physical processes doing stuff (for example, colliding with each other).

Real, live, messy humans fall into some weird liminal space, between all of these. But there’s a constant temptation to force them into one more familiar frame, or another. My kingdom for a model!

Of course, obviously these frames can be useful. We don’t need to think of Bob as having a single consistent utility function to think that he messed up by stabbing that pencil into his eye on a dare. And this despite Bob’s intransitive preferences about lizard stuff. So clearly, there is some way of thinking about real humans in these terms, without going too far astray.

But I think we should be wary of assuming that we know too much about we’re doing, when we do this. And when we start asking questions from the perspective of an agent/physical system in the midst of creating/interpreting itself – questions like “need I make sure that my preferences are transitive?”, and “what are my preferences, anyway?” – I think we should be especially cautious.

And I want to urge this same caution in trying to justify anti-realist ethics via a “game theory” frame rather than a “single agent” frame: i.e., in moving from “doing ethics/becoming coherent/whatever gets me more utility” to “doing ethics/becoming coherent/whatever helps various mini-agents living inside me get along better, and thus get more utility” (see e.g. my discussion of “healthy staple-clipping” here). This sort of switch is popular amongst many anti-realist rationalists I know, and no wonder. It allows you to not-already-have-a-utility-function, while still thinking in terms you’re comfortable with: namely, agents with utility functions.

And to be clear, I think this sort of multi-agent frame can be very useful, including in understanding ethical dilemmas like the ones discussed above. But if we take it too far, it mischaracterizes the “parts” in question: as I noted above, the relevant parts may lack the structure this model imputes to them. And while I think that “helping your parts stop burning what they care about in unnecessary conflict” is generally great, I don’t think it captures my full sense of what makes ethics worth doing. In particular, I think leaning too heavily on that frame can end up yet another attempt to “pass the buck” of decision: to be a vehicle of some pre-existing set of optimization processes, rather than a person in your own right; to ask something else what to do, rather than to answer for yourself. More on this in my next essay.

OK, so those were two accounts of why anti-realists should do ethics that I don’t see as fully adequate. In my next essay, I’ll try to get closer.

"Part of," because it's quite a large topic, and I'm setting aside lots of issues -- and in particular, understanding what it means to "make a mistake," if you're an anti-realist.

Granted, one needs to say something about what’s going on with weakness of the will, here. But I expect to be able to do so.

I expect this is the source, for example, of “open question” stuff. Thus, suppose we try to say, with some anti-realists, that what you “should do” is constituted by what you “would want to do in blah circumstances.” And suppose I tell you that in such circumstances, you’d want to kill babies. Does that settle the question of whether to kill babies? No. You’ve still got to decide. The territory is one thing. Your response is another.

“Ah,” say the realists. “That’s because you weren’t talking about the right sort of territory. There’s some ‘essentially practical’ territory, which consists of ‘should’-y properties and facts, irreducibly different from the standard story. If I told you that according to this territory, you should kill babies, then this would settle the question of whether to do so.” But would it?

See Chapter 2 of Nick Beckstead’s thesis for a nice discussion of this picture.

Some people go further, and start fetishizing simplicity to some more extreme extent (see e.g. my discussion of “simplicity realism” for some vibes in this broad vicinity). But again: in the context of anti-realist ethics, why such a fetish? And anyway, was that the problem with the slaveholders? That their values required too complex a description?

It does seem like ascribing goals/values to other people is importantly tied to predicting their behavior, but it also seems to license attributions of “mistakes.”

OK, OK, I exaggerate. Total utilitarianism isn’t actually about aiming at the lizards. Just: being willing to, if the time comes. (Which it won’t!) (We hope.) (But why should we hope that?)

If necessary, we could formulate this inconsistency more precisely: i.e., by rephrasing (3) as “If (1) is true, then (2) is false,” or some such.

If you don’t like the “morality game,” we can rephrase the example in terms of “I have most reason to,” or whatever. It loses some of its force, but the basic dynamic persists.

Here I’m borrowing from Michael Huemer’s “In Defense of Repugnance,” which I recommend to people interested in the Repugnant Conclusion.

Here, the name derives from the idea that if, for a fixed population, you have the option to improve the total and the average and the equality of the distribution, then you’d have to be actively against equality to pass on it (since presumably you like improvements to the total and the average, I guess?). I don’t like this name; nor do I think this principle especially obvious, but let’s go with it for now.

There's also some question of whether the transitivity of betterness is a conceptual truth; but I don't think that's the best terrain on which to have the debate.

Start with the Utopia. Then (per Benign Addition), make the lives of everyone in Utopia better, but also add, off in some distant part of the galaxy, a giant pit filled with a zillion zillion lizards, each living barely-barely worthwhile lives. Better for everyone, right? The utopians all agree: nice move. And the lizards, if you count them, would agree too. But note that you don’t even need to count them. That is, as long as you don’t think that creating the lizards is actively bad, you can just be focusing on the fact that you’re improving the lives of all the utopians, which seems hard to dislike, plus doing something either neutral or positive on the side (i.e., lizard farming).

(And note that if you say that it’s actively bad to create slightly-happy lizards, you can quickly end up saying that it’s betterto create beings with net negative lives than to create blah number of slightly-happy lizards, which also seems rough. And note, too, that to sufficiently advanced or happy beings, the best contemporary human lives might look lizard-like – barely conscious, vaguely pleasant but dismayingly dull, lacking in all but the most base goods. Do you want the aliens thinking of your life as bad to create, because too close to zero? If not, where and why does the line get drawn?)

But if there are enough lizards, then improving the lives of all the lizards by some small amount, plus bringing the lives of the utopians down to lizard-level, will end up mandated by Non-anti-egalitarianism. E.g., if there are 100 utopians all at welfare 100, plus a million lizards all at welfare 1, then putting everyone at 2 instead is a better total (2,000,200 vs. 100,010,000), a better average (2 vs. ~1), and a more equal distribution as well.

So by Transitivity, a sufficiently giant lizard farm is better than Utopia. (We can go further, here, and start adding in arbitrary Hells that get outweighed by the lizards. I’m going to pass on that for now, but people who like the repugnant conclusion should expect to have to grapple with it.)

I think this is known as “McTaggart’s conclusion,” but can’t easily find the reference.

Suppose you’ve got a great, hundred-year life overall. Now suppose we could make every moment of those hundred years better, plus give you an extra billion years in some slightly-net-positive state – say, some kind of slightly-pleasant nap, or watching some kind of slightly-good TV show that you don’t get bored of, or maybe you’re transformed into a slightly-happy lizard for that time but somehow you’re still yourself. Should you take the trade?

Hum, actually, I dunno. (Am I allowed to kill myself, somewhere in those billion years, if I decide that I want out? Will I still be in a position to make that decision? OK, OK, we’re stipulating that I wouldn’t want to, even from sort of idealized perspective or something. Do I trust that perspective? A billion years is a long time…)

OK, but suppose you do it, on grounds analogous to Benign Addition (i.e., it improves your existing life, plus adds something stipulated to be non-bad). But now suppose you can improve all that nap/TV/lizard time by some small amount, at the one-time, low-low cost of giving up ~everything you loved in your original life and napping/TV-ing/lizard-ing full-time. Higher total! Higher average! (Do we care about equality across the moments of our own life? I don’t; maybe the opposite.) Shouldn’t you do it? Note, for example, that the first hundred years of your life, at this point, are a tiny portion of the overall experience – the equivalent of the first three seconds of your hundred-year thing. Mostly, you’re a lizard. You had your great loves and joys back around the time multi-cellular life was evolving, and you’ve been a lizard ever since. Maybe you should focus on improving the lizard-ness? It’s really the main event…

Thanks to Ketan Ramakrishnan for discussion of this point in a different context.

These are sometimes called “impossibility results,” but often, “valid arguments” would do just as well.

Though Alexander is responding to a formulation of this dilemma that relies on a version of Benign Addition that doesn’t improve the lives of existing people, and which is therefore, in my opinion, less forceful.

Suppose we say it’s (slightly) bad to create someone whose life is positive, but below average. Then, at least if doing more bad things is more bad, and bads can trade off in standard ways, then you risk saying that it’s better to create someone with a net-negative life than to create a sufficiently large number of people with net positive lives (a violation of what I think is sometimes called “Anti-sadism”). Alternatively, if you say it’s neutral to create people with net positive but below-average lives, it sure looks like you ought to be accepting my version of Benign Addition above, given that it’s good to improve the lives of the existing people, and the creation of the extra lives in neutral. Also, if it’s neutral or bad to create net-positive life, then why is it OK to risk creating net-negative life when you e.g. have kids? Also, if it’s neutral to create a somewhat happy but below-average child, and neutral to create a more happy but still-below-average child, but better to create the second than the first, how do you deal with the intransitivities this creates? Do you want to start trying to say fancy stuff about incommensurability? Also, any appeal to the “average” is going to implicate “Egyptology” problems, where e.g. you can’t decide whether to have kids until you know what the average welfare was like in ancient Egypt, what it’s like on other planets, etc. In general, I recommend Chapter 4 of Nick Beckstead’s thesis for discussion of the various choice-points in trying to say that potential people don’t matter (or matter less). In Alexander’s follow-up to the review, he revises his position to ““morality prohibits bringing below-zero-happiness people into existence, and says nothing at all about bringing new above-zero-happiness people into existence, we’ll make decisions about those based on how we’re feeling that day and how likely it is to lead to some terrible result down the line.”

“But in the end I am kind of a moral nonrealist who is playing at moral realism because it seems to help my intuitions be more coherent. If I ever discovered that my moral system requires me to torture as many people as possible, I would back off, realize something was wrong, and decide not to play the moral realism game in that particular way. This is what’s happening with the repugnant conclusion.”

In particular, “just stay at World A” doth not an adequate population ethic make (population ethics aspires to do much more than to rank world A, A+, and Z), he’s going to want to hold on to other intuitive data-points as well; and Alexander doesn’t say what he proposes to do if the intuitive satisfaction he seeks actually is impossible (indeed, there are various proofs in this vicinity, which Alexander is aware of, so I’m a bit confused by his optimism here).

Alexander acknowledges that he is bound by the empirical implications of ethical principles he is committed to – for example, if he is committed to “suffering is wrong,” then he has to follow the evidence where it leads re: where there is suffering, including re: animals. That said, it’s not actually clear why this would be the case, on anti-realism: in principle, you could revise your ethical principles once you see that they lead (in conjunction with plausible empirical views), to counter-intuitive places.

For what it’s worth: while I think I’m more sympathetic to the repugnant conclusion than the average philosopher (though see: these folks), I’m pretty open to denying these other premises as well (though transitivity is probably last-on-my-list to deny). Indeed: I suspect that, in general, once you start getting more open to bounded-utility-function vibes (which I think we may need to get open to), and to the idea that some parts of your value system might not be willing to sacrifice themselves arbitrarily for other parts (even if the other parts try to jack up the stakes arbitrarily), then the repugnant conclusion will start to look much more optional (and premises like Non-Anti-Egalitarianism much more suspect).

Or perhaps, some set of concrete philosophers. MacAskill’s book, for example, has a real-world agenda.

At least not for reasonable ways of spelling out what these two principles mean.

This is the translation of the drowning child case, above, into policy talk.

Here the symbol “≻” means “is preferred to” or “better than” or some “chosen over” or some such.

As an example of someone who seems to me to take this sort of argument fairly seriously, see Yudkowsky here.

Yudkowsky’s piece is also tied to a related but distinct discourse about coherence, which has to do with whether philosophical arguments about coherence give us reason to expect that future, powerful AI systems will have whatever property in the vicinity of “goal-directedness” and “consequentialism” causes them (the worry goes) to seek power and maybe kill everyone. I associate this argument mostly closely with Yudkowsky (see here, here, and here; though see also section 2 of Omohundro (2008)), and there’s been a lively debate about it over the years (see e.g. Shah, Ngo, Dai, Grace).

This particular argument is about a certain category of empirical prediction (though exactly what sort of empirical prediction isn’t always clear, given that any particular pattern of real-world behavior can in principle be interpreted as maximizing the expectation of some utility function – see here for more). In the present essay, though, I’m mostly interested in the normative question of whether we (and in particular, the anti-realists amongst us) should be coherent. You could think that the future slides us relentlessly towards a world full of coherent (omnicidal), expected-utility maximizers, forged from all the free power that coherence supposedly pays out, without thinking that you, yourself, should go with the flow (compare with Moloch, evolution, and so on). Perhaps you, in your incoherence, are a dying breed. But does that make it an ignoble tradition? Must you make yourself anew, out of metal and math, into some sort of sleeker and colder machine? Need you succumb to all this … modernity? Rage against the dying…

Still, there are important connections between the empirical and normative debates. In particular, the empirical debate typically appeals to two sorts of processes that could reshape a system into a more coherent form: the system itself (or perhaps, some part of it, or some combination), and something outside the system (for example, a training process; a set of commercial incentives; etc). I won’t be discussing “outside the system” forces very much here (though I’d guess that this is where the strongest empirical arguments will come), but to the extent the system’s own self-modification is supposed to be an empirical force for coherence, the normative question of whether coherence should look, from the perspective of the system itself, like an important target of self-modification becomes quite relevant. That is, one key thrust of the empirical argument is basically supposed to be “coherence is free power, the system itself will want free power, so the system itself will try to become more coherent.” But if the “free power” argument is weak, from a normative perspective, this sort of reasoning looks weaker as well. And indeed, to the extent that “outside-the-system” argument runs along similar lines – “coherence is free power, the outside-the-system process will want the system to be powerful, so the outside-the-system process will modify the system to be more coherent” – this argument might look weaker as well.

Here I’m adding in more philosophical content than my typical conversation about this, to include more of what happens in conversations with myself.

This is similar to the strategy Alexander pursues in response to MacAskill. See also Ahmed (2017) for a more full-scale defense.

See also Huemer: “there are no known cases in which one should make a particular choice to prevent oneself from later making a particular perfectly rational, informed, and correct choice, other than cases that depend on intransitivity.” Using what I expect is Huemer’s notion of “rational” and “correct,” I think Parfit’s Hitchhiker would count as such a case.

This is a case I heard Johann Frick give at a talk at NYU in spring of 2017. Note the similarity to the Mere Addition Paradox discussed above.

This discussion is inspired by one in Huemer (2008), though he uses a different dominance principle.

Though: which do you want?

Well, really, it’s: Apples if my choice set is blah, Grapes if my choice set is blah, etc. But trying to pump some intuition re: confusion about what intransitive agents are “trying to do” overall.

Is it, maybe, actively counter-productive in this respect, insofar as it requires you to endorse some counter-intuitive and therefore unpopular conclusion?

The proof for the utility function version goes through the aggregation theorem in Harsanyi (1955).

> ethics typically implies some effort to systematize our pattern of response to the world; to notice the contradictions, tensions, and coherence-failures that arise when we do; and to revise our policies accordingly, into a more harmonious unity. But why do this?

I kept hoping that you would eventually explain why. Instead you kept talking about ethical intuition. I don't understand this at all. Why do philosophers continue to treat intuition as the benchmark for correctness? Where else does this work? Math? Science?

A yo-yo and a string cost $1.10, and the yo-yo is a dollar more than the string. Is the intuitive answer *really* the right one?

Or: What are we looking at when sunrise happens, the rotation of the Earth pointing our sky in different directions over time, or the Sun revolving around us? Is the intuitive answer *really* the right one?

I bring math and science up because, by relying on objective processes to verify claims, math and science have been *extremely* successful. Unless I've missed something, ethical philosophy as it's commonly practiced stands in stark contrast to these fields - we can be moral realists, anti-realists, utilitarians, whatever we like. You admit that your own intuitions clash with those of previous eras when you mention slavery; why continue to act as though your moral intuitions are important?

> And my sense is that more generally, he wants to avoid the sort of thing epistemic learned helplessness is supposed to protect against: namely, being tricked into stupid conclusions by listening to arguments.

Yeah, I definitely agree with your take there. That really wasn't Scott's best moment. Still, it's hard for me to be judgmental since philosophers are always doing this useless intuition thing; I wouldn't necessarily expect Scott Alexander to realize that on his own. Even without knowing why, he's noticing, correctly, that philosophers aren't making headway.

I haven't finished reading this yet, but section 3.1 ("Drowning children stuff") made me feel compelled to comment. That section makes it clear that "anti-realist" needs to be more clearly defined. For two major types of anti-realist that spring to my mind, there are very simple (albeit different) ways to respond to premises 1-3.

An error theorist like Mackie will just deny premises 1 and 2, and treat premise 3 as trivially true. Premises 1 and 2 are false because they erroneously presume the existence of properties which error theorists do not believe exist in this world—moral permissibility and moral impermissibility. Premise 3 is trivially true for the error theorist because moral facts don't exist, so of course there is no morally significant difference between letting a child drown in front of you and buying a suit instead of donating money to save a distant drowning child. There's also no morally significant difference between eating a sandwich and intentionally drowning a child, according to the error theorist. Again, this is because for the error theorist, there are no moral facts. The error theorist will admit there is some kind of difference between drowning a child and eating a sandwich, but it can't be a moral one, since that would imply the existence of moral properties, which the error theorist denies.

In contrast, an anti-realist who accepts Hare's universal prescriptivism—like Singer did when he wrote Famine, Affluence and Morality—would insist on giving up either 1, 2 or 3, because universal prescriptivism treats moral claims as universalizable imperatives that must satisfy a consistency constraint, and it's clearly inconsistent to accept 1-3.

Again, I haven't finished reading this article, but I feel like a lot of confusion could be avoided just by describing what you mean by anti-realist.